|

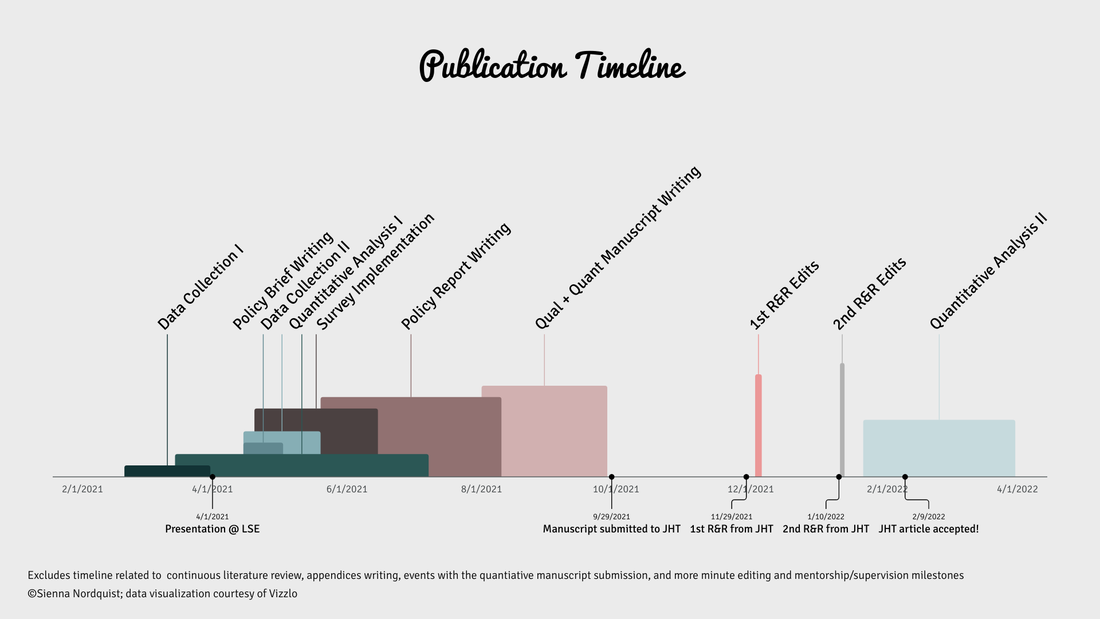

(Pub as in publication, not the English tavern!) In early March, I officially got my first ever (and first solo-authored) academic article published in the Journal of Human Trafficking! This is a major milestone for me, and one I could not have accomplished without the help of countless professors, staff members, and incredibly supportive friends and family members. As happens with achieving important personal goals, I have been reflecting in the past few weeks about everything the process of writing my dissertation at LSE (part of which turned into this article at the Journal of Human Trafficking) and navigating academic publishing taught me. Before this whole process began, I had only a vague idea in my head of what the conception to completion process of an academic article or paper looked like in actuality. I had been informed by professors that the timeline varies widely (usually nine months to two or three years – although there are always outliers that take even longer!), decisions by editors depend not only on the quality of your content and rigor of your research, but also publication timelines and the general direction of the journal; and the revision process necessitates an equal amount of perseverance as it does talent. While all of this information was useful and certainly steered my ability to submit my manuscript(s) at respected journals, I believe having a concrete, specific example of how a project went from an ambiguous idea to seeing it in print can be immensely beneficial in demystifying the publication process. Knowing what you’re getting yourself into (and how widely the publication experience can vary) can also set you up for reasonable, manageable expectations which keep you guided and motivated instead of demoralized. “It’s a marathon, not a sprint,” as they say at the LSE’s European Institute! In the below sections, I try to provide a detailed account of everything that went into this one publication and answer some questions I myself had about a year ago today regarding how this whole wild, intimidating publication process works. Buckle up, because there’s background context, a timeline infographic, and a list of top tips! Last disclosure before I begin: my dissertation was awarded a High Merit (69) and barely missed the Distinction (70+) categorization. Some students seem to believe if they don’t get a Distinction on their research paper or dissertation then it isn’t worth getting it published (tbh I was one of these students for the first 48 hours after I received my High Merit mark), but that is definitely not true. Research universities have a high bar for good marks (as they should!). As a student who has spent copious amounts of time trying to push the theory or findings of your field further, if you want to see your work published for others to build off of your findings, then go for it! Your work is meaningful because it is the product of a cumulative, scrupulous research process and you (most likely) have a fresh or needed perspective you can provide to the field. Moreover, you never know who your marker is or what their standards/points of comparison are, so put more stock in what mentors and advisors are telling you about the odds of your work getting published in a reputable journal over the individual mark. Or at least put more emphasis on what your later journal reviewers/referees say over a marker ;). Background context I completed a policy incubator dissertation at the LSE, which was a dissertation option unique to my MSc programme. The main difference was that I submitted two separate components (a Policy Brief in May of max 3,000 words and Policy Report in August of max 7,000 words) which summed to the normal LSE dissertation length of max 10,000 words. The dissertation was also more applied and policy-focused (as opposed to theoretical), as the name policy incubator implies, and the Policy Brief was geared towards a more informal audience than academia. My policy incubator dissertation investigated several anti-human trafficking policy outcomes in the EU. It started with a heavily quantitative focus (due to my undergraduate research training) and required an original data collection endeavor in various ministry reports and archives. Fortunately for me, being based at LSE’s European Institute gave me access to native speakers of many different European languages – several of whom were kind enough to volunteer their time to help me translate and read through some reports. (Needless to say, even when you’re working on a solo-authored publication, the whole process takes a dream team of support.) A few months into this quantitative work, having received positive responses from various ministries around the EU inspired me to design a survey to get a deeper impression of their policy perspectives and desires for future policy solutions and reforms. This added a whole new (yet smaller) qualitative leg to my dissertation research and writing process. Moreover, I realized fairly early on in my dissertation process (about early April) that I could make my policy incubator project rigorous enough to try and get it published after my time at LSE. This was a more powerful incentive than my mark (although as a highly competitive student, of course the mark was motivating me too); and once I designed and implemented my survey design, I decided to create two separate journal article manuscripts once my dissertation was completed: one which would encompass the quantitative analysis and findings, and the other which would display a critical analysis of my survey responses. It was this latter manuscript (the one about the elite opinion survey) which was published earlier this month! The following timeline shows the back-and-forth process between the policy incubator project and two separate manuscripts which unfolded over time. The manuscript with my quantitative analysis was also rejected by the first journal I submitted it to and I am in the process of re-doing major parts of the analysis now, which just goes to show that in some ways this process is never-ending. Background timeline September 2020 – I started coursework at the LSE and chose the policy incubator option December 2020/January 2021 – Conception of dissertation topic (human trafficking in the EU) Late January 2021 – Michaelmas exams due (research papers only) Late January/early February – Initial literature reading on human trafficking February to September – A continuous process of finding and reading new literature Late February/March – Data collection on quantity of human trafficking victims in the EU Late March – Generated initial quantitative results & end of Lent courses April 1 – LSE presentation before professors, fellow students, and some trafficking experts for initial feedback on theory + quantitative results April to May – Double checking data collection statistics and compiling new data Mid-April – Decided to conduct a survey amongst officials and NGOs who work on anti-trafficking policy in the EU and started draft of Policy Brief Mid-April to Mid-May – Typed up appendices related to my intricate data collection process and survey dissemination Mid-April to Mid-June – Heavy literature/theory writing for Policy Brief + Report Late April – Wrote survey to send to various EU policymakers and NGOs Early May – Received Ethics Board approval for the survey , submitted Lent research paper exam and Policy Brief Mid-May – Sent out survey to nearly 250 individuals and organizations (I wrote individualized emails for each recipient) & double checked original quantitative dataset figures Mid-May to mid-June – Followed up with survey recipients a maximum of 3 times before the deadline in mid-June Late May to Mid-June – Final outstanding Michaelmas & Lent Term exams due (online written exams due to covid) Mid-June – Collection of final survey results Late June – Initial mapping of policymakers’ preferences based on survey responses Early July – Finalized quantitative results for Policy Report July – Surgery appointments with a LSE graduate student to clarify my findings and make the dissertation more robust. And lots of writing up the quant/qual analyses while making frequent edits to the Policy Report Late July – Nearly final draft of Policy Report complete Early August – (Premature) celebratory trip to Scotland! Mid-August – Submitted policy incubator dissertation (quantitative analysis + some survey results included) August – Began drafting my qualitative/survey-based paper, which became the article published in the Journal of Human Trafficking Mid-September – Finished two manuscripts: one with the quantitative analysis and one with the survey analysis (which was sent to the Journal of Human Trafficking). Both manuscripts were submitted to separate academic journals Late November – R&R decision from the Journal of Human Trafficking with comments from three reviewers Early December – Manuscript with quantitative results is rejected after being sent out for review (albeit I did get the benefit of seeing the reviewers’ comments!) and I submit my revisions to the Journal of Human Trafficking for the survey/qualitative manuscript Mid-January 2022 – I receive a second R&R decision from the Journal of Human Trafficking and re-submit the manuscript with my revisions within a few days (the required edits were minor) Mid-January 2022 to present – Slowly revising my quantitative analysis manuscript to send to a different journal February 9 – The Journal of Human Trafficking accepts my manuscript! March 3 – My first academic article is published online! Why the Journal of Human Trafficking?

I chose to submit my survey results/qualitative analysis manuscript to the Journal of Human Trafficking for a couple of reasons. Most importantly, the content, direction, and interests of the Editorial Board clearly overlapped with my article. As “human trafficking” is obviously in the journal name, it is one of the best places to get research on human trafficking published, especially as a new and unknown author. While trafficking research can also fit into journals on law and economics, political science, and public policy, since my paper was not a hypothesis-testing one, I decided it was best to stick to a topic-centered journal over one designed for a broader social science field. And second, several of the articles I read for my own literature review were published in the Journal of Human Trafficking. Sending your manuscript to a journal in which several of your sources were able to successfully publish their work is a good indication the journal will also be interested in your paper. Finally, I should add I had nothing but a positive experience working with the editors at JHT throughout this process, so if you are also in the anti-human trafficking research field, consider submitting your work there sometime if it fits. Was the R&R process miserable? Not at all! Perhaps it was just beginner’s luck, but Reviewer #2 wasn’t scary. She or he provided thorough but respectful and truly constructive comments and criticism. There was nothing mean, degrading, or condescending about the process, even though academic Twitter has left me with a (likely heavily skewed) impression that a bad experience is the baseline far more than what I encountered. I also made sure I thanked the reviewers for their time, and had some specific, genuine statements about how they had helped me see things differently or in better way in my revision cover letter – which I am sure helped. Even though you have an anonymous relationship with the reviewers (if relationship is even the right word for it), being professional and courteous goes a long way, as in all relationships. And while I have no other publication experience to compare this one to, I found the process of preparing my original manuscript to be more mentally and emotionally draining than the R&R process. Top 5 dissertation/publication tips for other students 1. Read the journal’s stylistic preferences over and over before submitting I read the Journal of Human Trafficking’s guidelines countless times, while actively comparing them to my manuscript format, and I still had to reformat my tables after my initial submission to the editors. Takeaway: you cannot read the guidelines and stylistic preferences too many times! 2. Plan ahead, including building buffer time into your research schedule for editing and unexpected challenges 3. Take time out for self-care, reflecting, being imaginative, and celebration after it’s all done I think my research work greatly matured between my undergraduate and graduate school years because covid and lockdown forced me to set aside time to think creatively and differently about the research questions I was trying to address. That time of free thinking (or thinking upside down in the figurative sense) was what made all the difference and can partly be attributed to my “Eureka!” moment to also included an elite opinion survey in my dissertation work. 4. Attend surgery or office hour appointments! (and schedule them while you’re still problem free – you’ll probably have a research problem by the time the appointment arrives) 5. Ask both experts and non-experts for feedback An expert in your field or topic is likely to approach how they read your work and evaluate their arguments with a set of assumptions they have built up over time as a widely-read individual on the topic. Their criticism and ideas are highly valuable, particularly as you first approach your editing phase, but sometimes it can be equally valuable to have a non-expert pair of eyes give you their thoughts. Since they will approach your writing without initial assumptions, their prodding questions may force you to think about the fundamentals you have overlooked in your paper, or force you to think of a better and more nuanced way to defend your argument. Article overview In case you are interested in the actual findings from my survey, here is a short overview of my publication’s results: national rapporteurs in Northern EU member states are perceived to function better than those in Western and Southern member states; Southern European respondents placed the highest importance on the European Commission's Anti-Trafficking Coordinator, while Northern European respondents gave this position the lowest importance; Western and Northern European participants were most likely to agree with legalized prostitution, while Eastern European respondents were most likely to oppose it; and Council of Europe GRETA experts place the most importance on the ATC official. As this brief synopsis suggests, the survey findings in my paper encompassed attitudes and dispositions towards different types of prostitution policies (which are commonly used to address – directly or indirectly – trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation), perceived effectiveness of anti-trafficking national rapporteurs, views on the competencies and agenda of the European Commission and EU Anti-Trafficking Coordinator, and suggested domestic and EU-level policy solutions for the future. Why am I really excited about this piece (other than the fact I can be like “omg that’s my name!” at the top)? It’s replicable! Whether it is me replicating the survey in the future to focus on a different public policy area or on anti-trafficking elite policy preferences in another region of the world, or someone else/another team of researchers, I’m glad I’ve created a blueprint for how elite opinion formation (instead of a survey experiment or public opinion analysis) can be studied and analyzed at a regional level. Thanks for reading along and let me know which tips/insights were helpful, or if you have thoughts (good, bad, or whatever is in between) about my paper. Article citation – Sienna Nordquist (2022) EU Policymaking and Anti-Human Trafficking Efforts: Inferred Policy Preferences from a New Survey, Journal of Human Trafficking, DOI: 10.1080/23322705.2022.2041339 Blog citation – Nordquist, Sienna. March 22, 2022. “On getting a first pub.” <siennanordquist.com/blog>.

0 Comments

|

AuthorSienna Nordquist is a PhD Candidate in Social and Political Science at Bocconi University. She is an alumna of LSE's MSc in European and International Public Policy and was a Robert W. Woodruff Scholar at Emory University. Archives

April 2025

Categories |