|

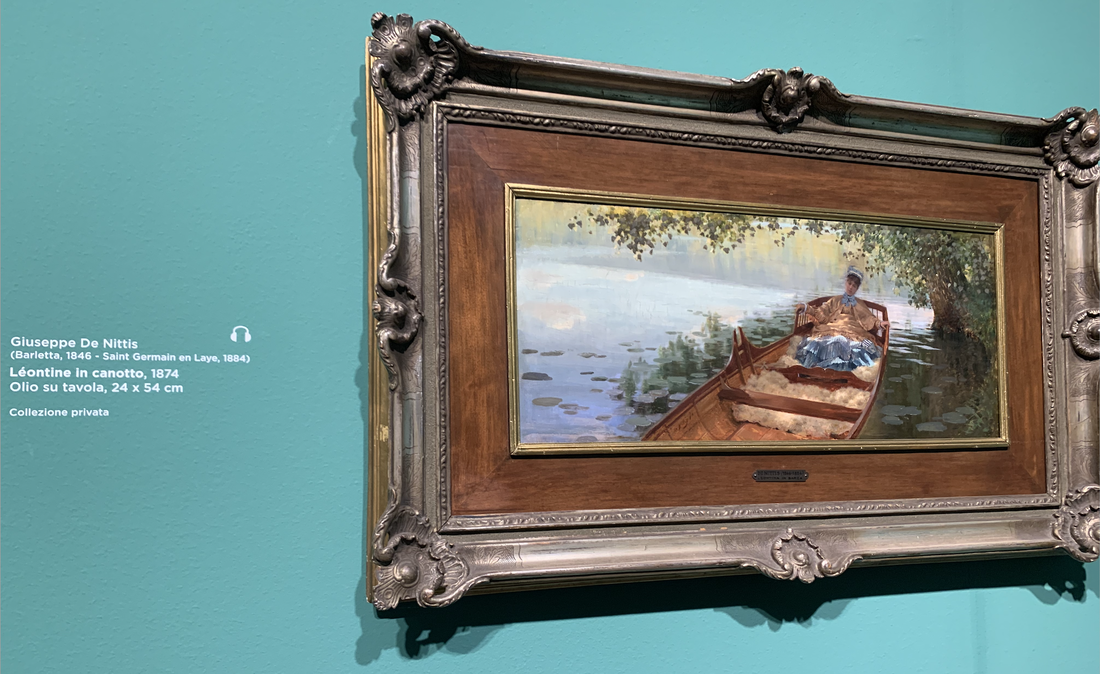

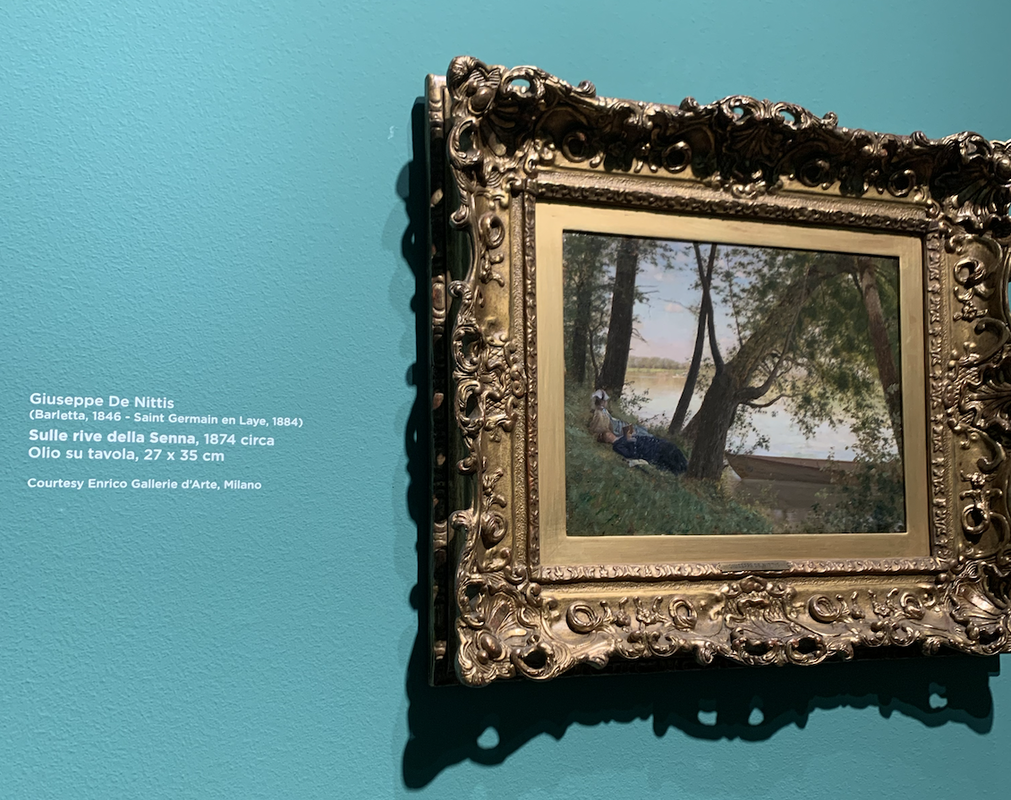

On a recent day trip, I had a chance to enjoy northern Italy’s unusually sunny March weather in Novara, Piemonte. I was initially drawn to visit Novara by the promise of the Castello’s “Boldini, De Nittis et les italiens de Paris” visiting art exhibit. It seemed rather fitting that an art display dedicated to famous Italian painters who lived and worked for most of their lives in France would be hosted in Piemonte – an Italian region bordering France, where you can even hear instructions announced in Italian and French on the local trains. I did, however, learn that if and when visiting a town known as the “city of the clouds,” you should expect massive throngs of people if you visit on an unusually warm spring day. Between the carnival, street food fair, and annual flower show, the city was jam packed. And with spring break and Easter approaching in Milan, there were similarly large crowds at Palazzo Reale for the twin exhibit “De Nittis: Pittore della vita moderna,” which I was inspired to attend after the other exhibit in Novara. Below is a summary of what I learned about De Nittis and modernist Italian painters in Paris from these two exhibits, as well as some short reflections. Disclaimer: My only art training is from an undergraduate study abroad course on Renaissance art, so take my opinions with a thick grain of salt. Giuseppe De Nittis – a renowned modernist painter – hailed from Bari, Puglia, where his family affectionately referred to him as “Peppino,” and later studied in Napoli before visiting Paris for the first time, falling in love with the city and culture, and later deciding to make it his permanent home. In shaping and showing modern life in Paris during the time of the world’s fairs/expos and industrial and urban change in the late nineteenth century, De Nittis and other Italian painters in Paris capture the energy and vibrancy of transformation. His wife – Léontine – was a frequent subject of his paintings. De Nittis’s earlier paintings in Paris reflect his youth and willingness to assimilate to French culture and daily life, while also networking his way into serious connections. Conversely, the later paintings show more of a focus on stillness, tranquility, and the peace that comes with escaping the city for country life. The most prominent takeaway from the Italian painters in Paris is the following: What’s ordinary can gleam. Not only is there physical glimmering from the bright yellows in Corcos’s La farfalla (1881) or the dazzling embroidery of Edoardo Tofano’s Passeggiata sul Bosforo (1879), but there is also the small joys that many of the paintings evoke. You can almost hear the deep music from Federico Zandomeneghi’s Il Violoncellista (1882), experience the laughs and shrieks of joy and fun in De Nittis’s La lezione di pattinaggio (1875), and feel the quiet and serenity of De Nittis’s Sulle rive della Senna (1874) and Léontine in canotto (1874). But you can also sense of how the “ordinary” shown by the painters was really a break with the past. The normalcy and quiet grandeur of the ordinary is drawn under a feeling of disquietude and change. Paris (and many other urban areas the artists drew, like London) was undergoing massive change at the end of the 19th century, and this is reflected in the busy-ness, societal standards, and intermingling reflected in the modernists’ portrayals of everyday life. While most of the paintings center on upper class or middle upper class life, you get the sense that the cities, expectations, and qualities of life/states of work were changing for nearly everyone. I was lucky to get to see these two juxtapositions up close and in two cities; the exhibit in Novara focused on a few of the most prominent Italian painters in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century, bringing masterful scenes/portraits of modern life to the halls of science, industry, innovation, and further trade flows. Many of the most famous paintings and portraits were completed in time to go on display for the world’s fairs in Paris, which were held in 1855, 1867, and 1878. The 1867 expo was particularly important for Italian painters’ arrival on the French art scene, as it marked the debut of De Nittis and Boldini, a modernist painter from Ferrara who studied art in Florence. And the other exhibit in Milan centered on solely De Nittis and his personal evolution over time, not the wider scope of transformation in Paris, France, and Italy. The breadth of De Nittis’s interests were clearer in the Palazzo Reale exhibit: there were paintings of Puglia and Napoli that were more prominent at the beginning of his career, and then even a Japanese inspired twist to his work towards the end. The differences between when and how De Nittis froze Campania and Paris in time with his art is staggering and speak to both his skill, and how different “change” looked in those places at around the same time. While the people in the foreground and background of De Nittis’s paintings are elite and wealthy in his stills of Paris, those in Napoli are visibly poorer. Take, for example, his incredible paintings of Mt. Vesuvius’s eruption in 1872, which he witnessed with his own eyes. It reminded me of Josef Rebell’s painting of Vesuvius erupting decades earlier (the painting of which I saw with my own eyes in 2019 at Milan’s Galleria d’Italia). Rebell’s painting makes the danger and destruction of Vesuvius seem far off and far away, the moon illuminating the perilous waves which keep the watcher away from the fire and smoke. De Nittis’s, on the other hand, focuses on the panic and bustle of people trying to get out of harm’s way, and the beauty yet terror that is evoked by the fact that Vesuvius upended or distorted everyday life in Napoli. But, again, the poverty and precarious economic state of those in the paintings of Napoli and Vesuvius seem to be emphasized, except for that of Pompeii’s Forum where, like today, the tourists at the ruins are dressed differently and come from a different background than the locals. (Although, I have to point out as well that tourists in the nineteenth century were much better dressed than those today, and dressed for a cooler climate than the baking Campanian sun I associate with Pompeii.) Back in Novara, the city is defined both by its proximity to and distance from Milano and Torino and its heritage from Saints Gaudenzio and Agabio. Gaudenzio and Agabio were the first and second bishops of Novara so there are paintings and statues in their honor in the Duomo and Basilica di San Gaudenzio. There are even pastries specific to Novara that are named after Agabio, so there’s lots of cultural connections to the saintly hero icons scattered around the città (including a quarter named after him). As with all nice day trips, they must come to an end at some point, and walking back to the Novara train station with several street names the same as those in Milan punctuated by reminders of Gaudenzio and Agabio reminded me how intertwined and distinct the cultures and histories of northern Italian cities are (and dare I say with French cities too). References

“Boldini, De Nittis et les italiens de Paris” exhibit at Castello di Novara “De Nittis: Pittore della vita moderna” exhibit at Palazzo Reale (Milano)

0 Comments

|

AuthorSienna Nordquist is a PhD Candidate in Social and Political Science at Bocconi University. She is an alumna of LSE's MSc in European and International Public Policy and was a Robert W. Woodruff Scholar at Emory University. Archives

April 2025

Categories |