|

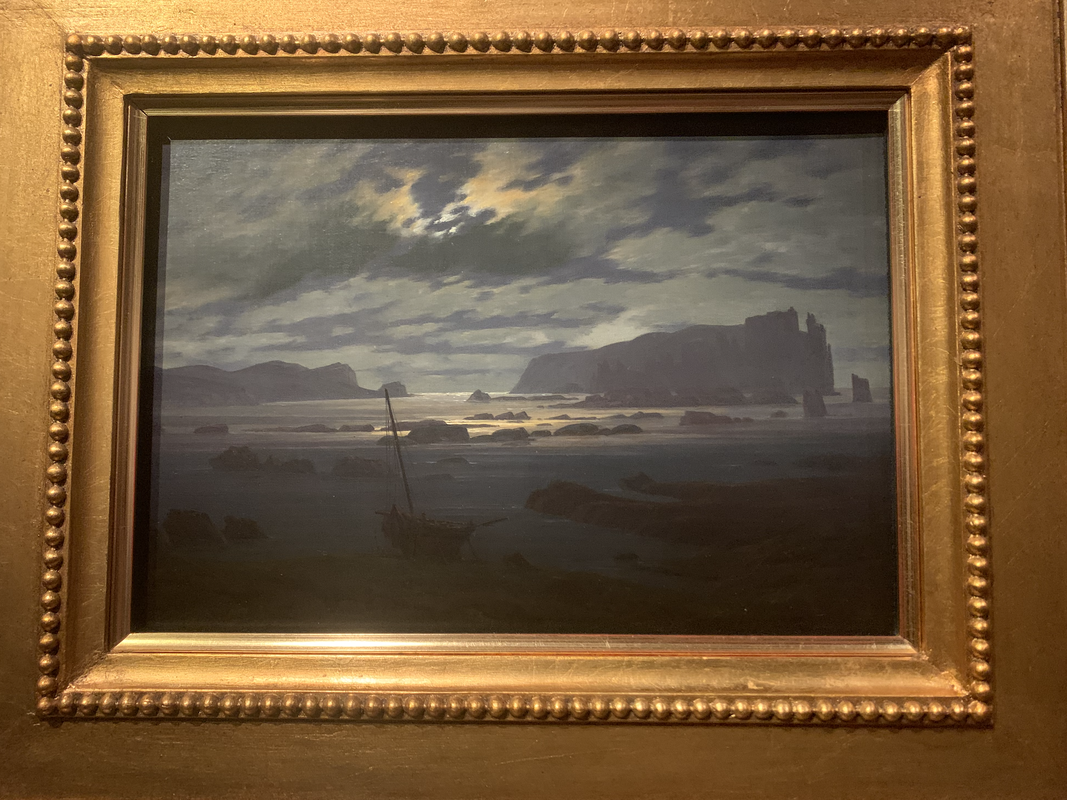

Since I haven’t visited NYC that many times in my life, none of the visits blur together like revisiting my hometown tends to do. One of the strongest memories I have of visiting NYC was the time I visited as a teenager and played “Welcome to New York” by Taylor Swift alone in my hotel room and looked out at the skyline with wonder; what a novelty both the view and Swift’s new album, 1989, were at the time. My recent trip in March was very different. It was my first time visiting NYC after university so it felt like my first “Real Adult”™ NYC trip. And as a researcher, there was a research component to my travels! I spent the Friday of my visit in the New York Public Library’s beautiful Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room consulting the CARE, Inc. Collection. (Yes, this is more Cold War related research. Look out for a co-authored academic publication hopefully sometime in 2026.) Shout out to Zola for not only hosting me, but also taking some time off work to be my archival support system for the day! Research trips really are more fun with friends! Lastly, this trip was an actual mini-vacation. My other trips always overlapped with debate tournaments and UN conferences (I am very fortunate), so this was my first time truly exploring the city, staying with friends, experiencing the first few days of spring weather, and seeing New York from the locals’ perspective. This, of course, including visiting a few art galleries, the two standouts of which were “Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature” at the Met and “Harmony & Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910-1930” at the Guggenheim. Caspar David Friedrich, a Scandinavian-German artist during Germany’s Romantic period, is probably most well-known for his painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). At least, that’s the only painting of his I knew before seeing the Met’s impressive special exhibit on his life’s work. In my eyes, the painting represents how the human-nature relationship is one of being simultaneously overcome by the expansive power of the natural world and reflecting on one’s ability to match or challenge it. Or, it’s about venturing into the unknown with the assuredness which faith inspires. Interestingly, having not previously known the title of the work, I think of the rocks first and the fog second. If the rocks are the real focus, then perhaps Friedrich was trying to inspire the viewer to take the challenges no matter the risk, or to find beauty in the unknown. These same themes can be found hidden in Friedrich’s earlier works too. Notably, sketches like Monastery Ruins at Oybin (1810) and Cross by the Baltic Sea (1815). Friedrich’s focus on places of worship and faith leads to a connection between spirituality, humanity/perseverance, and nature throughout his works. Although his later paintings, like A Walk at Dusk (1830-1835) are darker but also more reflective and evocative than some of his earlier portraits of nature in Pomerania. Pomerania, of course, reminding Zola and me (since we took German politics together) of Angela Merkel’s constituency. His paintings of the Baltic Sea also reminded me of my newfound bucket list item to visit there after hearing so many of my Berlin friends share their vacation stories. Outside of enjoying the Friedrich collection, we perused the Renaissance art, American collections, so many Monets and Degas that I had no idea were based in NYC, knights and swords, and Stradivarius instruments. You can easily spend many days at the Met, as you also can at the Art Institute in Chicago or Le Louvre in Paris. I was surprised to learn (from Google) that the Met’s collections are so much more extensive than those in Chicago or Paris, but in many ways it is difficult to rival the Big Apple. The building alone is a work of art too! And filled with lots of natural light. After being amazed, overwhelmed, and then amazed once more by the Met’s collections, we took a break to eat a late lunch in Central Park and browse Albertine for French books before setting off for the Guggenheim. The first Frank Lloyd Wright I’ve seen outside of Oak Park, which gave me a similar wave of joy as seeing a Calder statue in Normandy. The Guggenheim’s exhibit was focused on orphism, a new art term for me. Orphism was a period of abstract art – somehow related to Orpheus, but the exhibit’s explanation for this confused me – which deconstructed modern structures with shapes and colors. Between the circular nature of the Guggenheim’s winding path and the shape-shifting like cubes in many of the orphic paintings, I honestly felt a bit dizzy. And I’m probably not the target audience for abstract art, but I appreciated many of the placards which described how the orphic painters in/of Paris tried to deconstruct the relationship between place, space, time, and human experience through the movement. And how their own work was changed by their individual experiences in the First World War and jarring interwar period. Many sought refuge in new places or decided/were forced to fight, and it reflects in their work. Having recently visited Paris for the first time myself, I did, however, feel equipped to appreciate Robert Delaunay’s painting of the Eiffel Tower (1910) and the inquietude it inspires. Perhaps I’ve just gotten used to the cacophony of Milan but I was surprised by how quiet some parts of New York could be. How memories can stand still as the noise acquiesces into the past and out of our thoughts. Part of this could have been a function of enjoying a few days of reprieve after a conference and the archive work and before returning to the normal day-to-day of TAing and researching in Europe. But in the larger scheme of things, despite all the hustle and bustle in NYC, the wide array of simply endless opportunities and activities to do make the world seem quieter. Like each of us as individuals will find a spot in the city where we’re meant to be and find a day of adventure carved for each of us. Along with surprising moments of silence and clarity amidst the literal noise, time also seemed to stand still. Perhaps it was because the city was standing in between the cold of winter and promising warmth of spring, and the clocks moved forward an hour; but the stillness outpaced the changes. In a world that feels like it’s accelerating right into more geopolitical problems, the unexpected respite into calmness in NYC was refreshing on account of its abruptness. Thanks to all the friends who made my first trip back to NYC in 7 years so fun, memorable, and relaxing! I also appreciate how you all get me and made food the main attraction of each day with nice outings and sightseeing scheduled around the delicious meals. My kind of trip! :)

0 Comments

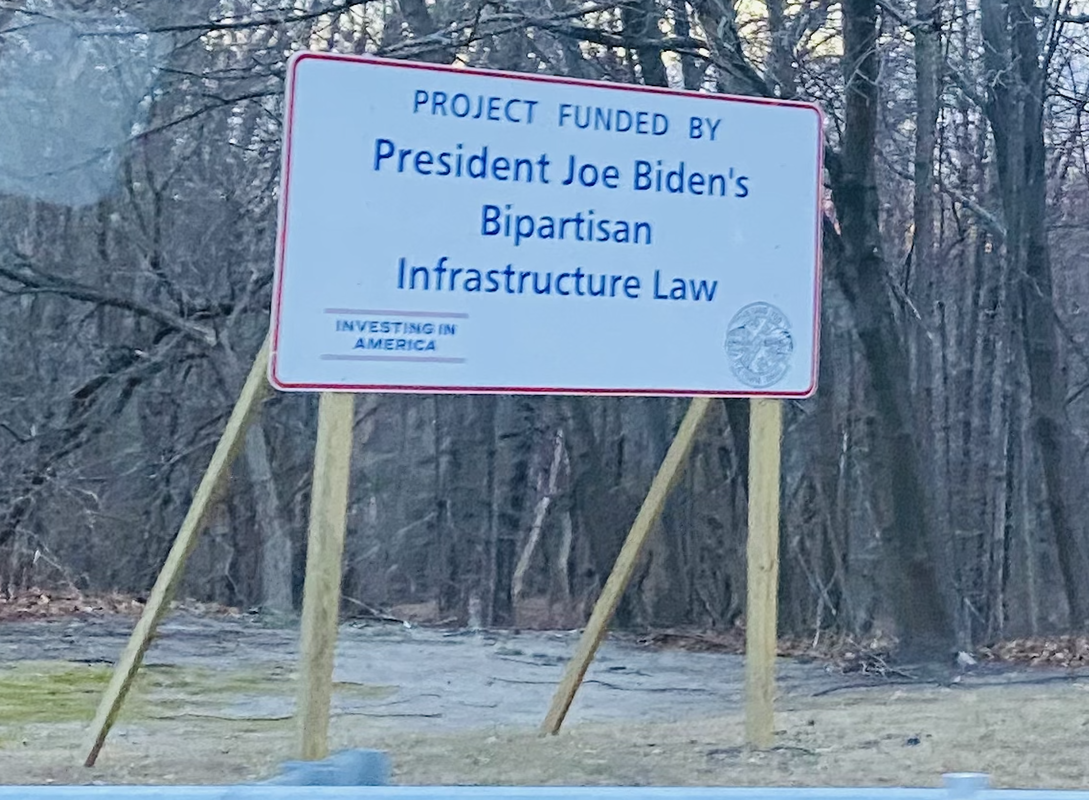

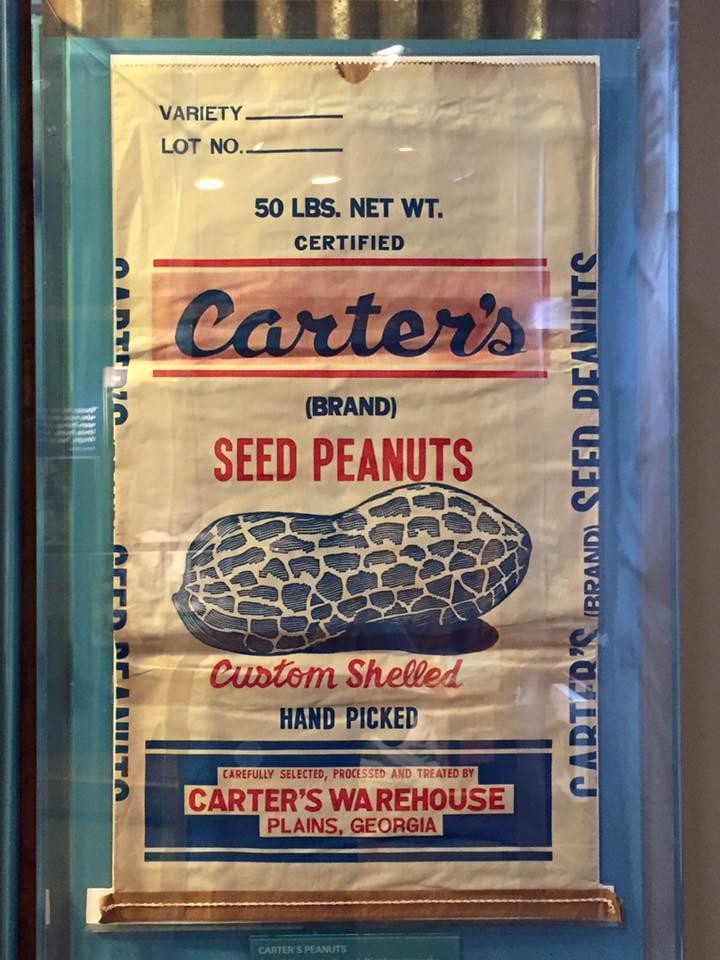

Or, On Two Polish Confessions, One German Mass, and a NAFTA Lunch When I was nine years-old, I was a co-student representative for my fourth grade class to our elementary school’s Student Government. For children, I think all of us in Student Government took our roles a bit more seriously than expected, but that was especially true for my co-representative and me. In addition to having a real policy platform – mine was for a student-run newspaper and recycling education – we took complaints from fellow students very seriously. After our grade started being reprimanded by the teacher aides in the cafeteria more often for loudness, we noticed that it was the new walls that had been built around the cafeteria which were creating echoes, and the aides were being disproportionately mean in how they were responding to some of the students. So, the co-representative and I scheduled a meeting with our school’s principal and the aides to discuss our concerns. Even back then, I was so convinced of the necessity of having empirical evidence to support my claims before making an argument, that I asked my dad (who was on the School Board and made the mistake of encouraging this type of behavior by asking my sister and I at dinner about things we would do to make our schools better) how I could come up with a math equation to prove that the cafeteria loudness was because of the walls’ echoing, and not the students. When he explained I would need calculus to do that, I asked him to teach me that. When he explained I would first need to understand basic algebra, I asked him to teach me that instead. If memory serves correctly, he did attempt to show me a few basic equations the next morning (which went over my head) and I realized that I wouldn’t be able to use math – at that time – to make my position. My co-representative had, unbeknownst to me, come up with an even better solution for making our case. He kicked off our meeting with the principal and all the “adults” by reciting his own version of the Gettysburg Address, complete with swapping in our names, changing the number of scores since the American Revolution, and fitting the language to our rather different situation! Our meeting was productive, the adults were impressed with our maturity and how we took our jobs are representatives and engagement with democracy so seriously, and ultimately things improved. Our elementary school had lots of branding around “Character Counts,” including the creation of pin badges. A few days after the January 6th Insurrection, I was still home from my year at the LSE (and would remain home for some time because of the new alpha Covid strain in the UK at the time) and cleaning out my childhood closet. I came across a satchel bag I had carried my books in throughout 3rd grade, pins on “Citizenship” and “Responsibility” still attached. Oddly, this stirred up a lot of emotions for me. I’m sure myself and every other American had a lot of feelings, mixed feelings, in the weeks after January 6, 2021, and the impeachment proceedings. One thing that stuck out in my mind was how far away from these basic values every part of government had become. How distant were days when two enthusiastic nine-year-olds could try to make the most of their representative positions and really feel that they were embodying the reality of American democracy. And, how I had no idea if these types of values were still being taught in school, or how one even could when there’s such a dearth of representation of character in nearly any institution. My argument in this piece is that the time from Election Day 2024 to Inauguration Day 2025 has similarly represented more than an interim. We were all Lame Ducks in this period, regardless of if people were happy, sad, or indifferent to the result and what’s to come, or what’s being left behind. I spent Election Night 2024 in Berlin, watching the results roll in at an official watch party with panel after panel of German party representatives, politics watchers, and high-level think tank analysts. I decided in the few days afterwards that, since I was going home from Europe for Thanksgiving anyways, I needed to soak in as much time in the US as possible. Mostly for my friends and family, who I miss very much, even if I’m out living a great life for myself doing what I love in Europe. But it was also to understand the America of this moment, as a person and as a political scientist. This blog is longer, more heartfelt, and personal than most of what I write. It’s because I think America deserves no less, and at least an attempt to capture what this interim period was like, both for those who are politically rejoicing, and those who are mourning. The blog also deserves deeper observations than the surface-level ones I could have also spent time dwelling on. (For instance, since when did everyone start reverse parking into parking spaces? I didn’t get the memo over in Europe.) I will leave my academic thoughts for future research work, which I hope will merit some grant investments and co-authorship one day on how recent events altered how Americans conceptualize foreign policy. In the meantime, I turn now to what I experienced traveling to Chicago, rural Massachusetts, South Carolina (via DC), Seattle, and back to Chicago again. Many friends and family have tried to very honestly tell me I’m probably the last person who can understand, since I’ve spent the better part of the past six years living out of the United State in continental Europe and the UK. I’m an insider looking out, not an outsider looking in. I leave this both as a caveat and a warning for finding too much meaning in what I’ve learned. But it’s meant a great deal to me, and I think it might mean a thing or two to someone else. In an effort to understand, and also to give thanks to the friends and family – a few of whom I agree with on everything, a few of whom I disagree with on everything, and the majority of whom we have some things but not others we agree on – who will always make America my home, let’s begin in the calm and cold of December. Christmas Carols & Lights One thing I always enjoy about returning home is how quiet and peaceful it is, especially in the wintertime. In true Midwestern fashion, my small hometown is closer to the prairie forest preserves than downtown Chicago, although it’s simpler to say I’m from Chicago. Amidst family time and catching up with friends, returning home also means enjoying walks in the fresh air, the harmony of the prairie ground, and occasionally being able to hear coyotes, illegal jet skiers on the frozen river, and early morning hunters. I like the constancy of returning and how very little seems to change. I hated how boring it was as a kid, but as an adult who is returning from another continent, there’s nothing more relaxing than knowing that nearly everything will be the same as it was. In visiting rural Massachusetts as my first stop out of town, I noticed something unexpected for the first time. While I’ve always been impressed by Chicago’s over-the-top Christmas lights and displays on many properties, I think New England does it better! Not only are there more houses that put up holiday decorations, but they are really well done and fanciful without being overbearing. I also like how New England houses have a tradition of lighting candles in each window, something I had only seen in movies until this year. That being said, there is nearly nothing as specials as the Chicago Botanic Garden’s Lightscape celebration for the winter holidays. What also struck me in rural Massachusetts that escaped me in my hometown was the pushback against Robert Putnam’s infamous “bowling alone” thesis. Community members not only come together to discuss faith, local politics, and HOA matters on a weekly or daily basis, but seemed to know and care about one another, even if they disagreed. It’s been a while since I had seen strangers make so many in-real-life efforts to get to know others, share food, and tell stories. It was uplifting and gave me hope in our communities and societies. We may still be more politically polarized than ever before, but there seems to be a willingness to still communicate and understand. At least in small towns. And perhaps it is out of necessity instead of willingness, but it’s still there. In one of these discussions, a political comment I heard is still sticking out to me, all these weeks later: “I mean, I voted for Biden twice and what has that gotten me?….oh whoops, I mean Biden then Harris, I still have whiplash. Well, in some ways I did vote about Biden twice.” The political scientist in me wants others to explore how many voters in general really felt a vote for Harris was about Harris, or about Biden… So little changes in my hometown. That being said, there was one notable change post-election that immediately leaped out to me. The Ukrainian flag that had been hanging with the American one outside my hometown church for more than two years had been taken down. I assumed it might be a direct consequence of the election, but after attending mass my first weekend back, I gained a different understanding. The Polish priest who had presided over the town parish for some time had passed away since this summer. He had kept the Ukrainian flag waving in our town ever since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. While I mostly grew up at an Italian-American church in downtown Chicago, and not in my hometown parish, I had started going to confession at my hometown church in the last few years. The Polish priest was nearly always my confessor on the rare occasions I returned, and I appreciated how every confession turned into him telling me a story about his childhood in Soviet-era Poland, despite these stories having no connection to the sins I confessed or spiritual themes I brought up. I had gone to confession a few weeks after January 6, 2021, and while I was still awaiting better circumstances to return to the UK for my studies. I was feeling distraught about the state of the US after Trump had been impeached but not convicted, and confession felt like the answer. I explained part of this to the Polish priest, and that I wanted forgiveness for how I was feeling about those on the other political side; those who were defending Trump after we came so close to losing the hard and soft institutions of our democracy on January 6th. “That’s not how this works,” my priest rebuked me. “What? I thought that’s exactly how confession works.” “You only receive reconciliation for sins. What you’ve confessed isn’t a sin. God permits us to have judgements about others, especially on actions they’ve taken that go against our morals and values. You are allowed to have negative opinions.” I continued to explain how I was feeling, and how I was worried our country might never come back together, both if Trump never faced repercussions for his actions, and in the likely event he came back to politics since he hadn’t been convicted. The priest went on say that I don’t get to take others' sins upon myself. That God forgives instantaneously, but his reconciliation is with those who have strayed away from him. Human reconciliation is more complicated, and longer. He shared how he felt his home of Poland was still experiencing a crisis of understanding its identity and coming together after its Soviet era. That being free from the USSR had saved it, but it also forced Poles to sit with, struggle with, and answer questions they hadn’t been allowed to ask before. We were sitting there across several generations, two different first languages, and many different perspectives, but he taught me something about humanity in that moment. Unity can’t be declared, or something to be led out of sometimes. Instead, it takes a lot of patient moments praying for good to prevail, and working for those who are brave enough to keep virtue in their hearts to have the chance to make a meaningful difference when the time finally does come. For my politics and me, we will still be waiting to see a day on the other side, but holding a candle to remind others of the values of liberty, freedom, and minority protections and human rights which democracy defenders have continued to web into our national culture since the American Revolution. And while the Ukrainian flag may no longer be flying in my hometown and many other American cities anymore, those of us who believe Ukraine has and continues to defend Western democracy since 2014 won’t give up on its right to exist, and in the value of Ukraine to all of our collective, free future. A lively DC I left Boston for South Carolina to see my extended family via DC. Traveling through Dulles on one of the busiest travel days of the year was a cultural experience in its own right. On top of the general busy-ness, I was struck by how nice people were. Both when they accidentally bumped into you, or vice versa, and chatting while waiting in long lunch lines for some food before the connecting flights. As I left one of many Starbucks options in my terminal, a Southern man declared the most genuine “pardon me, y’all” I have heard in a long time, including the few years I lived in Atlanta. I spontaneously texted one of my closest friends who lives in DC and asked if she just happened to be in Dulles at the same time as me. “I don’t live in DC anymore!” she texted along with Christmas greetings. I had forgotten that she moved for a clerkship at the same time that I moved to Berlin from Milan. How quickly all of our lives were changing and moving at the same time, especially friends I have in the political world. Wall Street in SC My time in South Carolina was mostly about family. All about family, and making new memories in the house I’ve known the longest in my life. Looking out from the top window on the staircase at the same street I used to daydream about as a toddler and a young kid. It makes me happy now to look out the same window, because I’ve truly grown up to be cooler than I ever even thought to imagine as a child. I think my younger self would be amazed I speak multiple languages, have had the good fortune to live in several countries and make friends around the world, and get to do work I love every single day. The drive from Georgia to South Carolina and back again is also so familiar that I wouldn’t need a roadmap. I used to travel from Atlanta to my grandparent’s home for long weekends while I was studying at Emory, and their proximity was such an understated blessing of going to university there, which had never been the plan. A reminder of how some of life surprises look like they were always meant to be; like life had planned itself better than you could. A small joy that I used to have in coming to my grandparents’ house was to read their local newspaper. I always found it interesting to see what the big “policy” issues of the town were – housing concerns, a lack of workers, too many tourists, new hot spots to visit – typically a microcosm of the “bigger” issues that are covered in the traditional outlets. This time, however, when I asked my grandfather at breakfast if I could see the local paper for the day, he told me they’re now out of business. “Why, why did you want it?” “Because I wanted to read it!” “You really liked reading it?” “Yes, it’s one of the things I always like about coming here.” “Oh, well apparently you were the only one, and you don’t even live here! They couldn’t make enough money so they closed.” Like my childhood-student-representative desire to see students get to publish their own thoughts on a smaller slice of the world, I suppose I am one of the last steadfast supporters of local printing and reporting, although I’ve never put money where my mouth is as I’m wholly reliant on the media subscriptions my universities have offered me over the years. Another appendage of democracy which seems to be losing its prescribed value. “Well, I guess I’m just left to the Wall Street Journal then.” Some other musings from my time in the South: I forgot how Southerners distinguish between their American family members in the North and the South, that the division of the country is still so much more omnipresent and epistemic there than in any other region. Southerners have an unrealized tendency to separate “family” from “my Northern family.” I also forgot just how exquisite Southern cuisine is, how nice it is to clothes shop in stores where it feels all the workers are hyping you up and truly trying to find you options that make you feel like yourself, and how delicious Southern ice cream can be. It was also telling how much Hurricane Helene’s devastation came up so casually in conversation. It left so many communities reeling and still affected, the same way the Palisades fires predominate conversations only a few weeks later, and what they mean for our future climate, health, and economy. Farewell to the Chief Back to the normalcy of Chicago, working remotely on my PhD, and catching up with some old friends, I was struck by how hard it was to watch America’s sendoff to Pres. Carter. As an Emory alumna and someone who volunteered at the Carter Center for a year, he left an impression on me as a person. Both getting to witness his humility many years after being the most powerful person in the world – I would see him eat normal cafeteria meals alongside the volunteers if he and Mrs. Carter were in town – and seeing his commitment to teach today’s young leaders about American politics. While his politics were despised at the time, much ink has been recently spilled on how his presidency was better than remembered. If nothing else, he played an important role in trying to center human rights as a part of America’s foreign policy and trying to help a new generation of leaders see human rights as a fundamental and worthwhile part of America’s story and destiny. Which is why the stark contrast of the solemnity of America’s farewell ceremonies and stoic effort to bring his remains to the Rotunda – the same one where Trump is inaugurated today – to Trump’s press conference at the same time where he did not rule out military action against Canada, Panama, and Greenland/Denmark is so blinding. As an IR scholar, I think we’ve officially entered a second Cold War era, and one where the US is willing to treat even allies as adversaries in the 4D game of international chess. This isn’t only antithetical to Pres. Carter’s image and memory, but those of nearly every postwar president which treated the transatlantic relationship as something sacred and special, if not annoying but necessary.

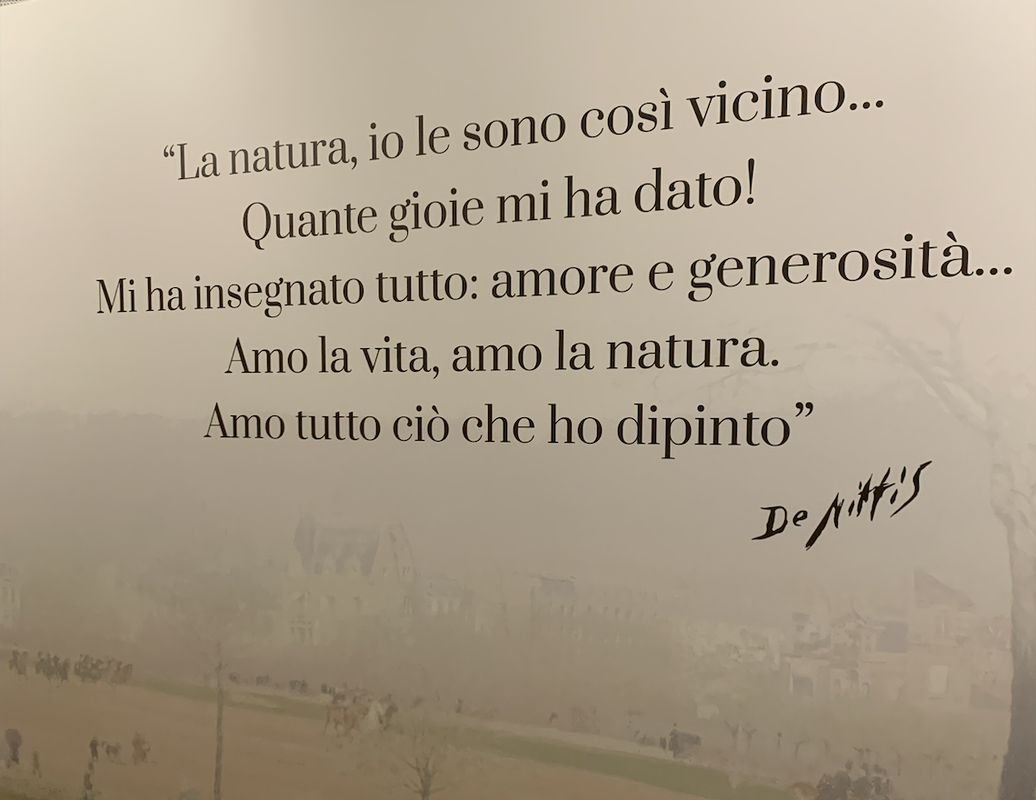

Island Thoughts While some of my friends back in Italy went to tropical climates for the holidays, I definitely had the coldest beach experience of the bunch. After my time in Chicago, reminiscing and working, I traveled West for the first time in eighteen years. My destination: Seattle, WA for a girls’ weekend with one of my closest friends from college, who I hadn’t seen since our senior year spring break turned into a permanent Covid break. Having never been to Seattle or Washington State, I was struck by the hipster attitude it’s known for, high prices, but also the amazing skyline. I don’t know what I was expecting from Seattle, but whatever it was, the city far surpassed it! I loved seeing my friend’s favorite spots in the city and her neighborhood, and access to Puget Sound and the Pacific Ocean is just amazing. From the hills to the forest, the Cascade Mountains and Mt. Rainier in the distance, the fresh air and surprisingly clear water, it’s spectacular. (Plus the coffee and fresh fish are top notch :) ). My favorite part of the trip, however, was how we made use of a rather sunny and warm day (for January in the Pacific Northwest) to visit Whidbey Island. Only a long drive and ferry ride away, we got to see a terrific view of the Pacific Ocean from several different angles, explore the Deception Pass State Park, and receive ominous text messages from our data providers that we had crossed into Canada (we hadn’t, but we were very close!). Lunching with NAFTA After exploring the incredible vista from Deception Pass Bridge on Whidbey Island, my friend and I went to the only real lunch option we had – The Mill. For context, The Mill is advertised as an American-Mexican restaurant with a menu size that rivals The Cheesecake Factory and no discernible way of specializing in both American and Mexican cuisine. It is next to the Auld Holland Inn, a Dutch-inspired hotel that even boasts remakes of the giant wind mills. Inside The Mill, it appears that two completely different interior designers controlled its renovation. One put up the characteristic Instagram-y neon lights and floral décor, complete with the most amount of “inspirational quotes” (Be Brave; Hard Work Pays Off) in a women’s bathroom I’ve ever seen. Another focused more on the Dutch, American, and Mexican cuisine theme of the joint, complete with the old wood and fake stones that must have characterized the inn it used to be. (If anyone famous enough to ever get a “Lunch with the FT” column is reading this, The Mill might be the perfect spot for their writers; Edward Luce, hit me up for more recommendations.) It was a true Alice-in-Wonderland like experience. We weren’t quite sure what was meant to be real and authentic, and what was kitsch. It also managed to be our most expensive meal of the entire weekend, but lent itself as a great spot to catch up while also being curious about the décor! I also couldn’t help but feel like I was lunching with NAFTA, between the weird coverage of American and Mexican cuisine, and close proximity to Canada. When I first landed in Seattle, the first thing I saw was a giant group of American troops waiting for their baggage. I joked to my friend when I met up with her that I was wondering if we were invading Canada already (I half-joked, I was unfortunately half-serious too.) Fortunately, for now at least it’s just that there is a Navy base close to the border. Given that it was Trump himself who negotiated USMCA – the replacement trade deal to NAFTA – which expires in 2026, it will be ~interesting~ to see what becomes of American-Mexican-Canadian ties heading into our joint 2026 World Cup. German Mass Flashback

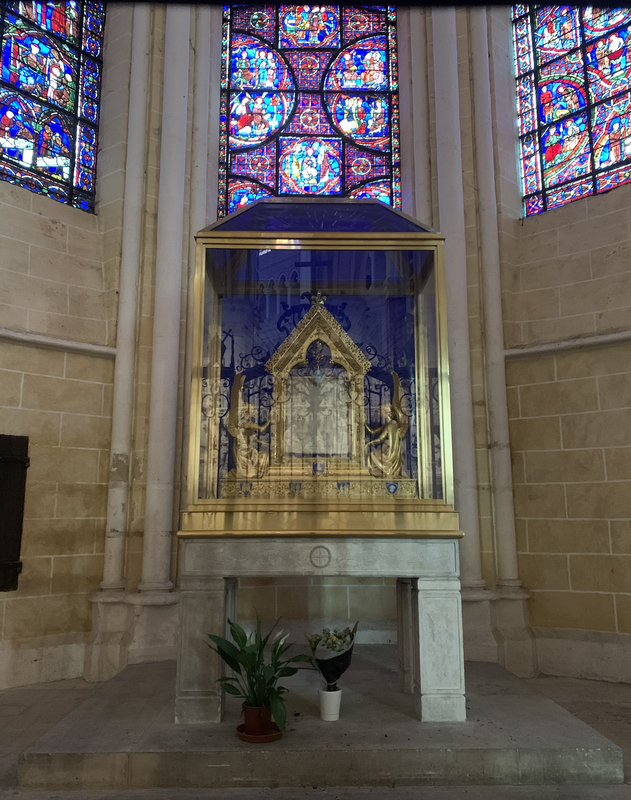

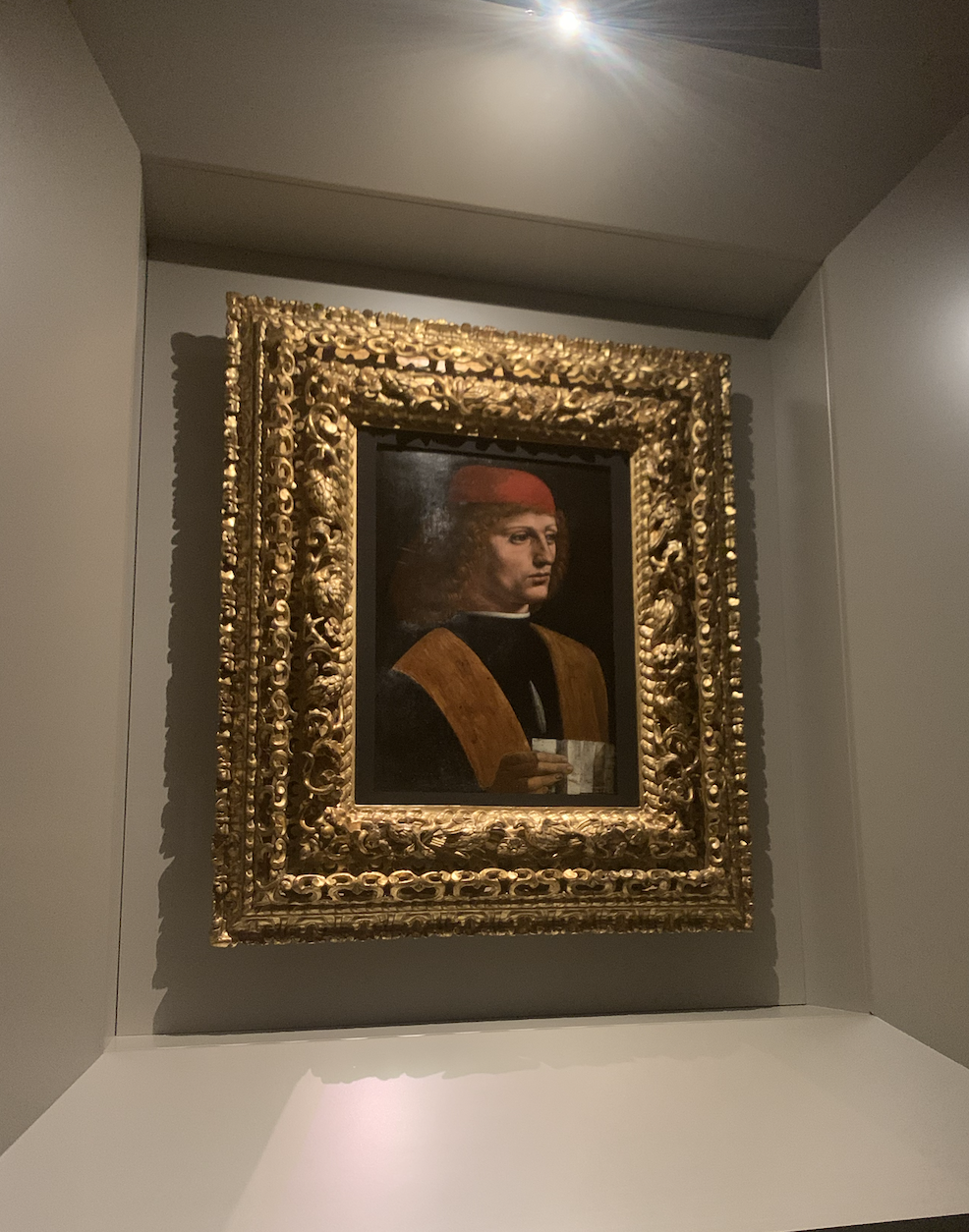

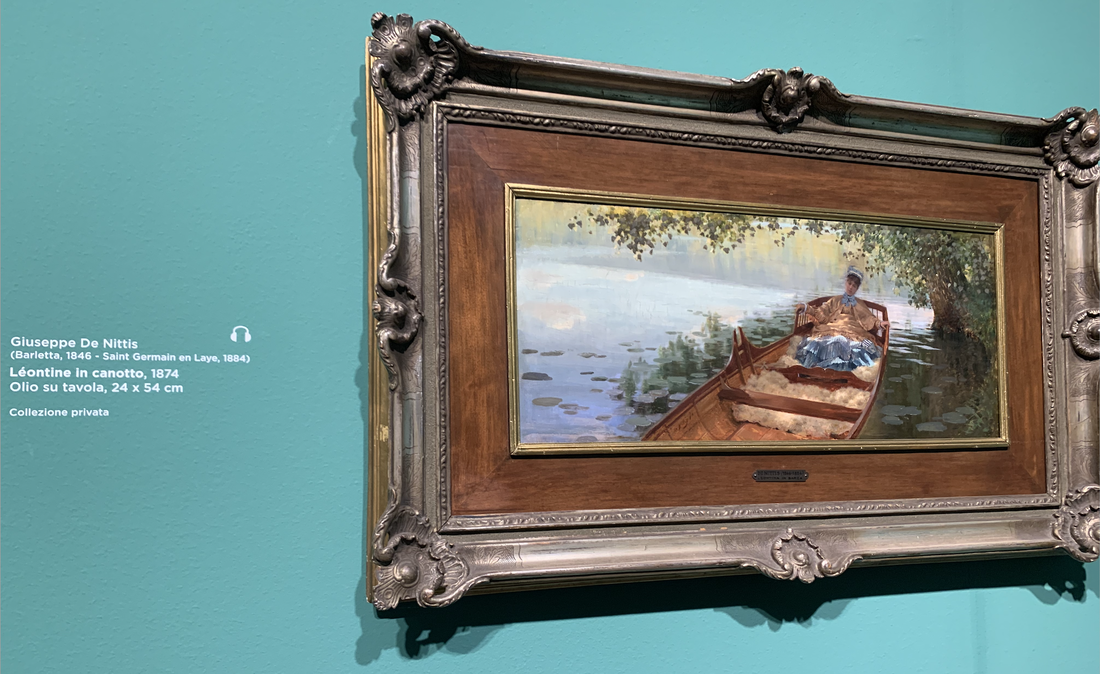

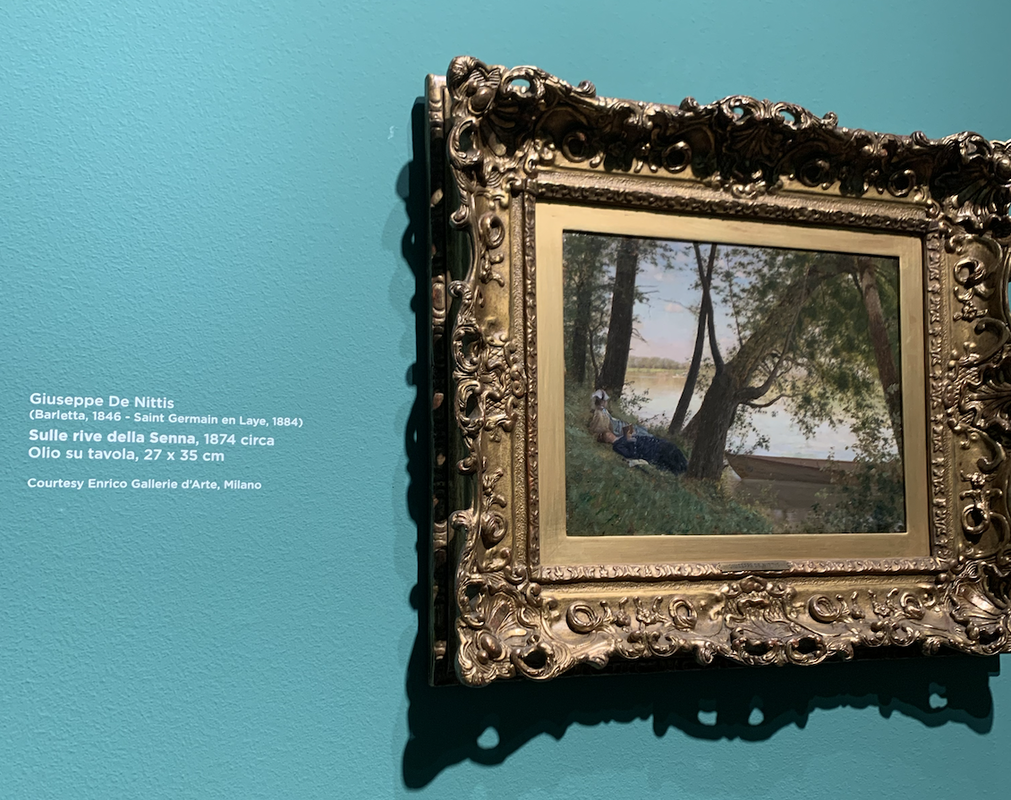

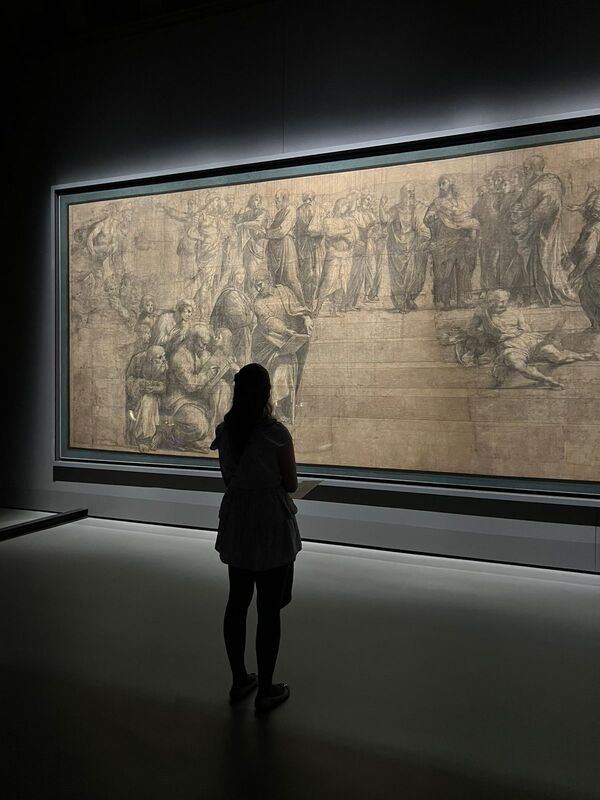

As I prepare to return to Europe from Chicago, now that I’ve rested from my own unexpected bout with the flu and norovirus, I can’t help but think about Election Night itself and the week afterwards. The panel after panel of German party officials I watched that night gave me absolutely no confidence that German politicians were up to the challenge that either administration would confront them with, but especially a Trump one. This has been complicated by Musk’s wading into the upcoming German elections, and shocking divisions in the current traffic light coalition over funding to Ukraine. The US is heading for a lot of tumultuous years ahead, not that the last few have been particularly peaceful or unifying. But Europe is heading for even choppier waters ahead, particularly since Germany is struggling economically and politically to take on a leadership role in the EU at this critical time. I went to mass the Sunday after Trump’s election and the collapse of the traffic light coalition. It was one of the few churches in Berlin that offers a mass in English for immigrants, most of whom are Nigerian, American, and British. The Nigerian priest – who was truly wonderful and always had great anecdotes to share – saw how fearful the congregation seemed after so much political upheaval and uncertainty around Ukraine, European energy and security, and economic growth. He asked us during the reading of the Prayers of the Faithful to name our fears aloud, which many in the congregation did. Then, we were instructed to sing all the verses of the final songs, and with joy in our heart. Mass ran no less than 30 minutes overschedule with all of this emoting and singing. One of my closest friends in Berlin had agreed to wait for me outside for a coffee after my mass. When I finally emerged he said, “What the heck were you guys doing in there for so long.” “Singing with joy from our hearts,” I said with a laugh. “What?” “You know times are bleak when the priest makes the German mass sing with joy from their hearts!” The whole episode reminded me of how important the words of faith and spiritual leaders can be in dark moments, even if they are impersonal. I thought about the Polish priest back home, who I didn’t yet know had passed away. I thought about how maybe I might return to confession with him, and hear if he had any advice for navigating the next four years as someone feeling discouraged by the state of the world, but also committed to trying to understand it in a scientific and empirical way – the same way I wanted to approach being a student representative all those years ago. I have no follow-up confession story with him, except my second favorite, which was that one time I listed out a long list of my sins in an act of reconciliation. His point-blank reply was “is that all?” As the news returns to lots of daily chaos and confusion, may we find that joy in our hearts each day. Each of us reminded of the values that matter to us most and the people we work so hard for. And finally in returning to the original theme of childhood thoughts on democracy and being back home, I started to wonder how the youngest of Gen Z feels about this interim period. As an “old” Gen Zer, I called my teenage brother to see if he had any thoughts or feelings about Inauguration Day. He said of course he did, but he and his friends don’t talk politics and they aren’t supposed to in school. He said he wished he knew more about what was going on, and that he felt weird about the inauguration because everything seems so “two sides.” I don’t want to speak for him, but he seemed to be picking up on how polarized America is, and has been since he was very young. He said one thing he was sure of, however, is that he’s happy to live in a democracy. I couldn’t agree more. My recent whirlwind trip through 6 countries and 7 time zones in 13 days and with 4 working languages (definitely a new personal record) with nearly all my worldly possessions in tow got me thinking about what makes or breaks an adventure. I was moving from Milan to Berlin via France (to crash my mom’s vacation – more on that later), which required a transatlantic flight to get back to Europe via London, two and a half days to pack and clean a flat, and then a thirteen-hour night bus from Milan to Paris. After the Parisian dream (my first time there!), I then took the Eurostar (my very first!) through France and Belgium to Cologne, and from there continued on a Deutsche Bahn train to Berlin. The night bus experience was certainly made authentic by the French teenager who spent the whole night of travel elbowing me in his sleep or watching TikToks without headphones on. But even with the tiny annoyances like that, plus how the bus drivers smelled profusely of cigarettes the whole ride, the experience was far more magical than grungy. How else can I describe entering France for the first time by reading “Mont Blanc” by Percy Shelley while going through Mont Blanc itself? Or suddenly being jolted awake by a stop in Dijon at 5:30 AM, with the first streams of light breaking over the imposing structure of the Dijon Cathedral? Or falling back asleep, only to wake again to the sight of hay bales in Auxerre that looked like they were lifted straight out of an impressionist masterpiece. (My first thought was, “Wow, they really look like that?!” because somehow, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a hay bale in real life before that moment.) Small, varied, and distant castles then seemed to accompany our bus along the last and final stretch from the countryside to Paris – reaching Vincennes at a still early 9:20 AM. Adventures are full of magic, and the magic comes in letting go of the small bad parts and embracing the spontaneous (and often improvised) good parts. Maybe an adventure is also tagging along on someone else’s for a little while; seeing the world through their eyes, and seeing what they value from their perspective. And then it’s seeing the same thing but finding a different aspect to be remarkable or perhaps even brilliant. For instance, my mom was interested in visiting key places in St. Joan of Arc’s life and death, so we toured Riems, Chartres, and Rouen. Each place had something special: the center of the French monarchy’s coronations in Riems, the Virgin Mary’s veil that was gifted by Charlemagne’s grandson to the village in Chartres, and the burial place of the heart of King Richard the Lionheart in Rouen. But what I found very special was a Calder sculpture that my mom and I literally stumbled on by accident in Rouen outside of the town’s Musée des Beaux-Arts. In elementary school, I fondly remember reading The Calder Game and loving the mind puzzle of connecting clues and art. (The prequel – Chasing Vermeer was equally good if my memory serves me well.) My native Chicago is also the seat of Calder’s Flamingo statue, so I enjoyed thinking that I could be like the main character and decode my surroundings in Chicago and the Midwest. Anyways, seeing an unexpected Calder seemingly so out-of-place in Normandy with its chilly sea-salt-air brought a giant smile to my face. And it reminded me the importance of having exposure to art, stories, and mysteries when you are young. A “room mom” in elementary school used to periodically come into our lessons and teach us about different world famous painters and time periods. She had studied art history before becoming a mom to one of the boys in my class, and would give us biographical information about a painter and then have us interpret or say what we saw in projector images of their most renowned art pieces. (Yep, we still had projectors and no Smart Boards until later.) I remember being thoroughly bored by these lessons – which I feel bad about now that I’m older, a teacher myself, and realize how much time she must have put into volunteering as an art historian – and wondering why I was looking at images of still fruit. In hindsight, however, knowing that art was something I was supposed to appreciate made me slightly more open to it as a grew older, so that by the time I was an adult, I actively wanted to learn more about other cultures and experiences by looking at things like art (and listening to music, reading books in other languages, etc.) Teaching is a sacrifice, as is writing for an audience, and the investments that teachers and authors made into me as a student and reader gave me the ability to make connections, feel a deeper connection to an unknown and new place, and experience happiness many decades later. Adventures are also about endings and beginnings. At the Louvre, I saw Da Vinici’s Mona Lisa with my own eyes. This marked the final major work of Da Vinci’s that I was yet to see! I started a journey to view each of Da Vinci’s most important masterpieces when I took an art history course on Da Vinci and Milan in 2019. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing Da Vinci’s The Last Supper and visiting the tree he used to sit under at what is now a conference center close to Santa Maria delle Grazie, and decided I would try to see each of his great works in my lifetime. This lead me on a five-year journey from Milan to Parma to London to Washington, DC, and finally to Paris with many repeat stops in Milan along the way. (N.b., the Sala delle asse is still not fully open in Milan’s Castello Sforzesco, but I’ve at least finally gotten to see part of it on some recent museum trips. The full room to be experienced later!) I truly expected that this feat would be something that took nearly my entire lifetime to do (or, at least, ten years). Getting to see it all in five years was both an act of intent and a happy accident. (Well, being lucky enough to attend the universities I did/am and to live in Europe at my age sometimes feels like some combination of luck and right timing, as much as it took many years of hard work to get to where I am.) And standing there in front of the Mona Lisa, both further from it and closer to it than I anticipated, I didn’t feel any extreme emotions, simply contentment. Contentment in working hard enough, living life fully enough, and merely being gifted enough blessings in life that I have seen so much beauty and wonder for myself. And reflection and love for all the people that have visited Da Vinci works with me over the last half decade; study abroad friends with whom I saw La Scapigliata in Parma, an old friend who took an early lunch break in DC to see Ginevra de’ Benci with me, my mom who saw The Virgin of the Rocks cartoon in London’s nearly empty National Gallery with me during covid times, etc. Meanwhile, a different journey I inadvertently set myself off on five years ago to collect individual Marshall Plan projects data in West Europe continues with some (more) planned archive trips in Germany leading me to a new and fresh start in Berlin. Whether or not officials recorded – and then left to posterity – highly specific economic records on Marshall Plan disbursements is unfortunately outside of my control, unlike Googling the locations of famous Da Vinci works. If anyone owns a time travel machine, then please let me know.  To celebrate the end of our first quarter, our PhD cohort went to a free quartet performance inside of Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Getting to listen to classical music while sitting next to Da Vinci's Portrait of a Musician was quite spectacular. Thanks to Ximena for capturing this photo of me looking at Raphael's cartoon for The School of Athens afterwards! Finally, a word of redemption for the Parisians and French. After having it drilled into my head by Americans, Brits, and Northern Italians for most of my life that the French/Parisians are the meanest people on earth, they were nothing but the loveliest strangers I have ever met in my life. They went out of their way to help us whenever we needed it, sometimes sat and chatted with us just to be nice, and were all around just deeply, incredibly kind. Perhaps it was post-Olympics euphoria or joy from the optimism the Paralympics brought to town, but we had literally zero negative experiences the entire week; while I’ve had mostly positive experiences in every country I’ve ever visited, each has normally had at least one outlier experience with a stranger. One café owner not only spoke to me in French and was incredibly pleasant to my mom and me, but he also had TTPD playing in the background (if you’re a fellow Swiftie, then you’ll understand the gravity of this.) The Parisians were also far more willing to speak in French with me than the Milanese are to speak in Italian with me some days (and I am nearly fluent in Italian while I am admittedly poor at French still). In Chartres, the café owner and our tour guide even cheered for me when I pulled out some (simple) French. It was the sweetest thing, and I hope the Parisians are an example for how you can encourage someone to keep going, and keep trying. That’s how we open up, show up, and share ourselves and our culture with others. Finally, it made me feel like my London lockdown attempt to teach myself French had not been in vain; another (happy) ending in learning coming back to offer assistance and a gift years later. On a recent day trip, I had a chance to enjoy northern Italy’s unusually sunny March weather in Novara, Piemonte. I was initially drawn to visit Novara by the promise of the Castello’s “Boldini, De Nittis et les italiens de Paris” visiting art exhibit. It seemed rather fitting that an art display dedicated to famous Italian painters who lived and worked for most of their lives in France would be hosted in Piemonte – an Italian region bordering France, where you can even hear instructions announced in Italian and French on the local trains. I did, however, learn that if and when visiting a town known as the “city of the clouds,” you should expect massive throngs of people if you visit on an unusually warm spring day. Between the carnival, street food fair, and annual flower show, the city was jam packed. And with spring break and Easter approaching in Milan, there were similarly large crowds at Palazzo Reale for the twin exhibit “De Nittis: Pittore della vita moderna,” which I was inspired to attend after the other exhibit in Novara. Below is a summary of what I learned about De Nittis and modernist Italian painters in Paris from these two exhibits, as well as some short reflections. Disclaimer: My only art training is from an undergraduate study abroad course on Renaissance art, so take my opinions with a thick grain of salt. Giuseppe De Nittis – a renowned modernist painter – hailed from Bari, Puglia, where his family affectionately referred to him as “Peppino,” and later studied in Napoli before visiting Paris for the first time, falling in love with the city and culture, and later deciding to make it his permanent home. In shaping and showing modern life in Paris during the time of the world’s fairs/expos and industrial and urban change in the late nineteenth century, De Nittis and other Italian painters in Paris capture the energy and vibrancy of transformation. His wife – Léontine – was a frequent subject of his paintings. De Nittis’s earlier paintings in Paris reflect his youth and willingness to assimilate to French culture and daily life, while also networking his way into serious connections. Conversely, the later paintings show more of a focus on stillness, tranquility, and the peace that comes with escaping the city for country life. The most prominent takeaway from the Italian painters in Paris is the following: What’s ordinary can gleam. Not only is there physical glimmering from the bright yellows in Corcos’s La farfalla (1881) or the dazzling embroidery of Edoardo Tofano’s Passeggiata sul Bosforo (1879), but there is also the small joys that many of the paintings evoke. You can almost hear the deep music from Federico Zandomeneghi’s Il Violoncellista (1882), experience the laughs and shrieks of joy and fun in De Nittis’s La lezione di pattinaggio (1875), and feel the quiet and serenity of De Nittis’s Sulle rive della Senna (1874) and Léontine in canotto (1874). But you can also sense of how the “ordinary” shown by the painters was really a break with the past. The normalcy and quiet grandeur of the ordinary is drawn under a feeling of disquietude and change. Paris (and many other urban areas the artists drew, like London) was undergoing massive change at the end of the 19th century, and this is reflected in the busy-ness, societal standards, and intermingling reflected in the modernists’ portrayals of everyday life. While most of the paintings center on upper class or middle upper class life, you get the sense that the cities, expectations, and qualities of life/states of work were changing for nearly everyone. I was lucky to get to see these two juxtapositions up close and in two cities; the exhibit in Novara focused on a few of the most prominent Italian painters in Paris at the end of the nineteenth century, bringing masterful scenes/portraits of modern life to the halls of science, industry, innovation, and further trade flows. Many of the most famous paintings and portraits were completed in time to go on display for the world’s fairs in Paris, which were held in 1855, 1867, and 1878. The 1867 expo was particularly important for Italian painters’ arrival on the French art scene, as it marked the debut of De Nittis and Boldini, a modernist painter from Ferrara who studied art in Florence. And the other exhibit in Milan centered on solely De Nittis and his personal evolution over time, not the wider scope of transformation in Paris, France, and Italy. The breadth of De Nittis’s interests were clearer in the Palazzo Reale exhibit: there were paintings of Puglia and Napoli that were more prominent at the beginning of his career, and then even a Japanese inspired twist to his work towards the end. The differences between when and how De Nittis froze Campania and Paris in time with his art is staggering and speak to both his skill, and how different “change” looked in those places at around the same time. While the people in the foreground and background of De Nittis’s paintings are elite and wealthy in his stills of Paris, those in Napoli are visibly poorer. Take, for example, his incredible paintings of Mt. Vesuvius’s eruption in 1872, which he witnessed with his own eyes. It reminded me of Josef Rebell’s painting of Vesuvius erupting decades earlier (the painting of which I saw with my own eyes in 2019 at Milan’s Galleria d’Italia). Rebell’s painting makes the danger and destruction of Vesuvius seem far off and far away, the moon illuminating the perilous waves which keep the watcher away from the fire and smoke. De Nittis’s, on the other hand, focuses on the panic and bustle of people trying to get out of harm’s way, and the beauty yet terror that is evoked by the fact that Vesuvius upended or distorted everyday life in Napoli. But, again, the poverty and precarious economic state of those in the paintings of Napoli and Vesuvius seem to be emphasized, except for that of Pompeii’s Forum where, like today, the tourists at the ruins are dressed differently and come from a different background than the locals. (Although, I have to point out as well that tourists in the nineteenth century were much better dressed than those today, and dressed for a cooler climate than the baking Campanian sun I associate with Pompeii.) Back in Novara, the city is defined both by its proximity to and distance from Milano and Torino and its heritage from Saints Gaudenzio and Agabio. Gaudenzio and Agabio were the first and second bishops of Novara so there are paintings and statues in their honor in the Duomo and Basilica di San Gaudenzio. There are even pastries specific to Novara that are named after Agabio, so there’s lots of cultural connections to the saintly hero icons scattered around the città (including a quarter named after him). As with all nice day trips, they must come to an end at some point, and walking back to the Novara train station with several street names the same as those in Milan punctuated by reminders of Gaudenzio and Agabio reminded me how intertwined and distinct the cultures and histories of northern Italian cities are (and dare I say with French cities too). References

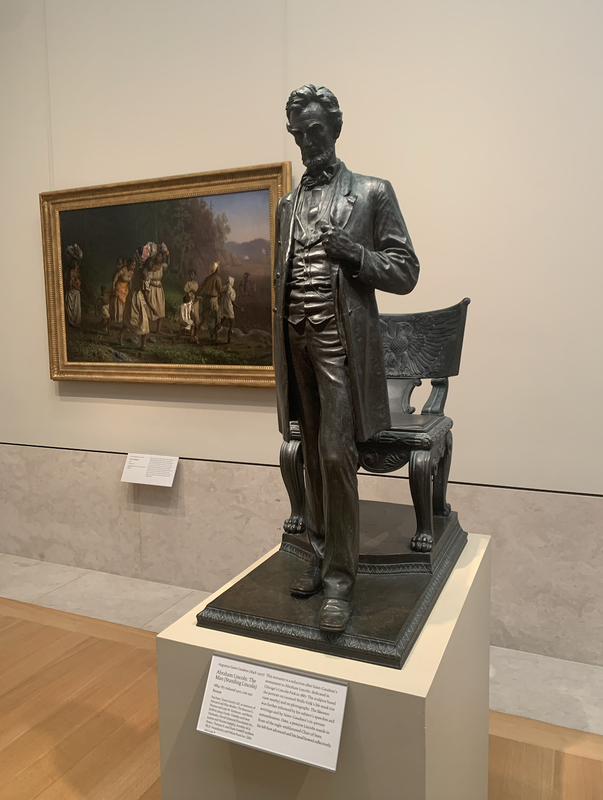

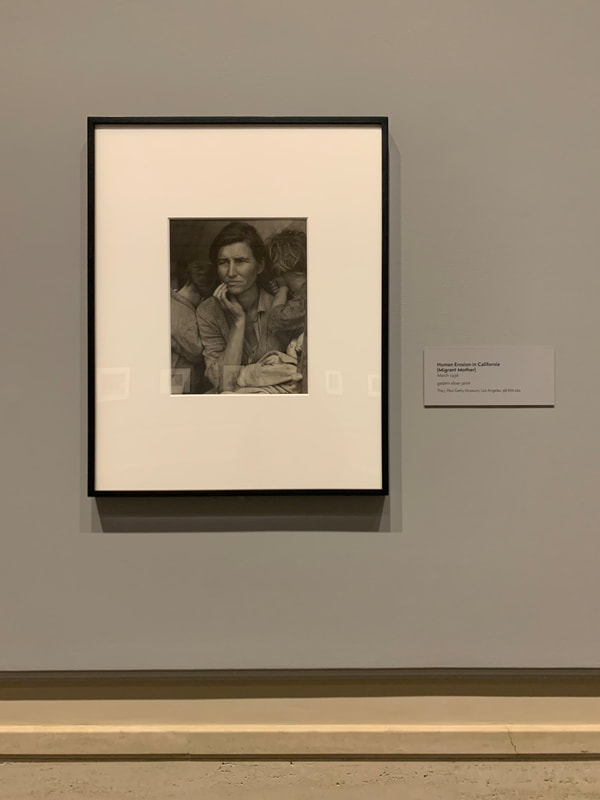

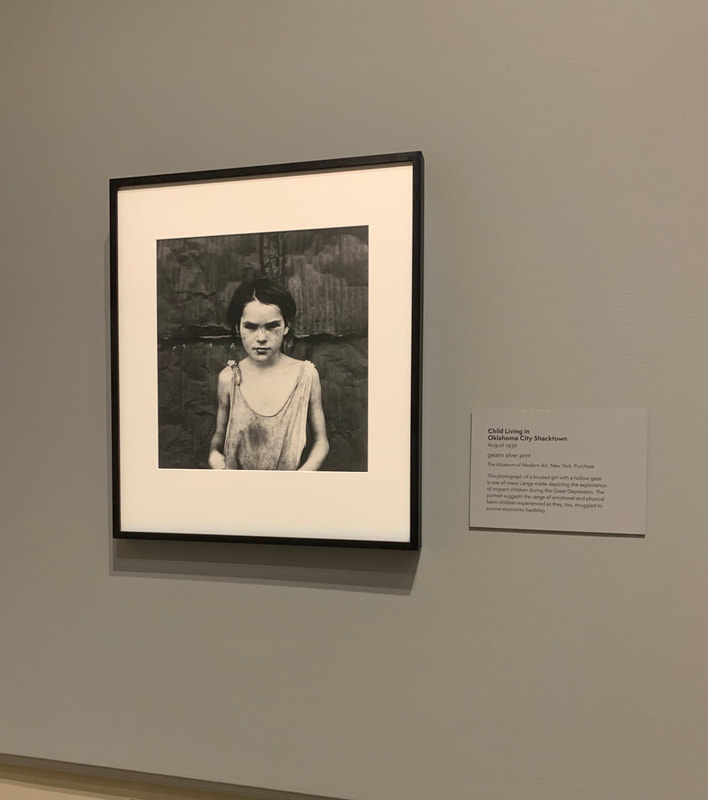

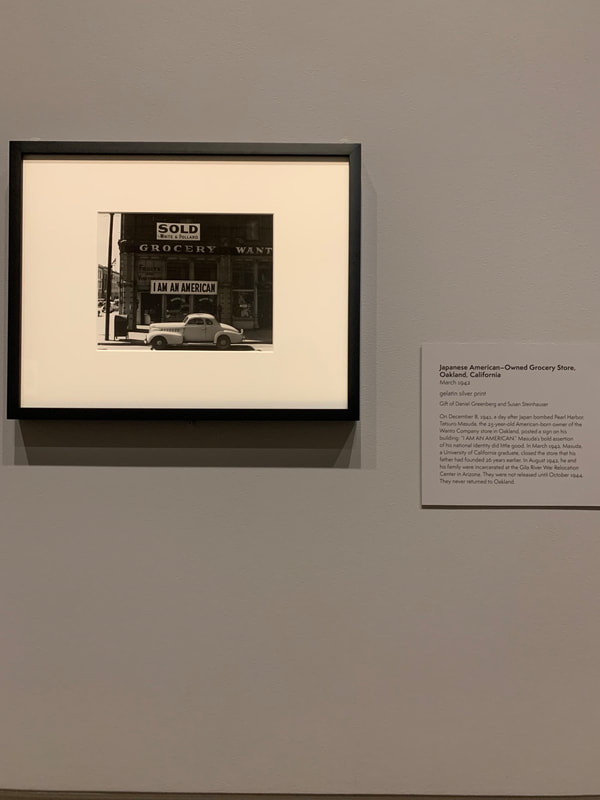

“Boldini, De Nittis et les italiens de Paris” exhibit at Castello di Novara “De Nittis: Pittore della vita moderna” exhibit at Palazzo Reale (Milano) A few weeks ago while in Washington, DC, I had the good fortune to see the National Gallery of Art with a close friend who I hadn’t seen in person for seven years. The experience reminded me of the importance of friendship, how having close relationships isn’t defined by space and time, and that art from many different eras and cultures tries to get us to tap into that humanness that connects us to others. It was also a lesson in how you may end up in surprising places with people you expect, or in ordinary, regular places with people you never anticipated meeting. Getting to walk through the art museum with my friend was a full circle moment, especially since that is something we did together in Chicago about 8 years ago, long before we had any idea what our lives or careers would look like. The day hit home that in some ways, the people that matter in our lives are constant, living paintings in our lives. We see them change, grow, and become more amazing than we ever thought possible; more frankly, we see them age and mature. (Although, as a counterpoint, I have to say my friend really did look like she hadn’t aged in the 7 years since I last saw her!) Friends reflect ourselves in a way that impersonal art can’t and their faces are more familiar than the strangers on the expensive walls of an art gallery. Sure, our friends don’t open up our world to allegory or metaphor, but they do embody who we were years or months or days ago when we first met, and who we hoped to be, and how we imagined our friendship could span the (short or long) distance in space and time. Friendship shows us the way more than we give it credit for. And real friends, genuine friends, are rare, as the adage goes. Rarer, I would argue, than DaVinci paintings, Michelangelo statues, and Rubens portraits added up across the world. Friendship reminds us of the promise we had in the past, what we’ve realized in the present, and humbly and more importantly, humorously – steers us towards better decisions. Or at least helps us make fun of our funny slip ups! Art reminds us of the same things…faded smile lines in images of those enduring immense suffering; chips in paintings that were once pristine and unblemished; marble Roman faces which to us are now pale, but were once in radiant color. The formal and informal art around us also reflects the phases and changes we all go through. The Joan of Arc Series by Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel portrayed St. Joan of Arc as young, mature, strong and vulnerable. The sunlight dripping from Titian’s ceiling mirrored the noontime light streaming into the museum. Dorothea Lange’s photographs reflect the hardship of the Great Depression and made me wonder what photography from the COVID-19 pandemic captured. How many of those expressions were also held in the US, UK, Italy, and around the world? My friend also taught me that you should pay just as much attention to the frame as you do to the painting or portrait it was carefully selected for. This seems like a good life lesson too: the frame you put around your life and its opportunities shapes and defines them. And your frame of reference or frame of mind may just entirely transform the environment you create for yourself and others.

On March 10, Bocconi University in partnership with the BLEST Lab and the Institute for European PolicyMaking hosted The Future of Europe Conference. This very special event brought together high-level representatives of European institutions, member states, and think tanks for a discussion of what Europe’s governance, macroeconomic, and sustainable future looked like. Since each of the panels involved lengthy speeches, debates, and (at times) combative Q&A’s with the audience, I decided to devote separate blog posts to the Governance and Macroeconomics panels. This one focuses on the proceedings from the Macroeconomics panel, which was chaired by Prof. Elena Carletti of Università Bocconi and involved Michala Marcussen (Chief Economist of the Société Générale Group), Kalin Anev Janse (CFO of the European Stability Mechanism and European Financial Stability Facility), and Ugo Panizza (a professor at the Geneva Graduate Institute). These reflections do not represent my own opinions, but those of the panelists I quote, and is an effort to share and communicate the current mood and thinking of expert European economists on the health and future of the economy and financial system in the present moment. If you read Part I of this blog, then you will notice that the headings of these reflections are the same, although the Macroeconomics panel took their thoughts and recommendations in a very different direction than the Governance one. In my view, they are equally insightful and revealing!

Reflection #1: Treaty reforms inspired the most enthusiasm, and the biggest ideas. While none of the panelists were supporting or detracting from calls for fiscal union in the EU, Panizza did suggest that, if such a step were to occur, it was the massive capitalization of the NextGenEU funds (referred to as PNRR in Italy) that broke the taboo in EU institutions influencing and injecting money into member states’ fiscal policy. However, with the ECB taking on a more and more discretionary role in member state financing through policies of quantitative easing (QE) and outright monetary transactions (OMT), Panizza worries the ECB is becoming the “fiscal watchdog of Europe.” Marcussen added later on that all the current proposals for common EU debt suggest dividing the fiscal union into ‘normal’ and ‘excess’ levels of debt such that in times of fiscal downturn or crisis, states are still responsible for solely their own ‘excess’ levels. Such measures are supposed to calm fears of the 'Frugal Four' (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden) that fiscal union would lead to precarious spending across the bloc and tie their sovereign wealth to fiscal impropriety by other member states. Marcussen also brought up how it may be wise to create mechanisms of some kind for governments to have access to safe funding at all times, instead of only having access to the ESM in times of crisis. Concerns over the fiscal health of member states and the EU more broadly also remain from the Covid-19 shocks, and those from the war in Ukraine and resulting energy crisis. Prof. Panizza was very frank in describing how debt-to-GDP ratios are at more elevated levels than they were before the Great Recession, and accelerations in GDP which bring this number down may be due to inflation, not real growth. While the spreads between bond yields in Eurozone countries remain relatively low, the markets can judge the economic health of the entire system incorrectly. The largest and most explicit calls for reforms came from Janse. Janse argued that the treaties should be reformed such that the ESM is accountable to the European Parliament, instead of the individual member states, as it is currently. However, it should be noted that the ESM, in its current design, is highly accountable to the national parliaments, and as such is an intergovernmental institution. Reflection #2: More Europe, but also smarter/“strategic” Europe. For Marcussen, the economic risks from de-linked fiscal and monetary policy strategies are only part of the need for more Europe in macroeconomics. The other reason is that challenging geopolitics along with high inflation and shorter economic cycles will make economic transitions more volatile and unpredictable for economists and experts to manage. Janse made the position that European institutions like the ESM are better positioned from US-centered or even global institutions like the IMF. (To my own surprise, the ESM is apparently better capitalized than the IMF.) The ESM also works similarly to the IMF, with countries in fiscal distress and undergoing market exclusion able to access precautionary lines but under conditionality measures of structural reforms. The ESM has a hugely positive brand with private lenders, which has led to low “market stigma” and helped to create the view that ESM lending is critical to investors trusting new and re-investments in states that go to the ESM for help. It was raised by Goulard in the audience, however, that part of why ESM reforms (like being brought directly into the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU) might not be implemented is because more mechanisms, like the ESM itself and open monetary transactions (OMT), are created and work. From this perspective, creating more institutional European mechanisms to respond to crises has instituted much-needed emergency instruments, but prevented having more difficult conversations about long-term institutional reforms that are necessary. Goulard referenced at this point fervent debate in France over Macron’s plans to raise the retirement age; a policy change and reform we now know quite literally burst to the surface of French politics after Macron invoked article 49.3 of the French constitution to ram through the raised pension age. Her main point was that macroeconomic funding needs to not only be dedicated to creating new instruments, but most importantly to investing in the future (such as in education). Reflection #3: America was front and center, in good and bad ways. In Marcussen’s opinion, the US overstimulated household income with its Covid-19 relief policies, whereas the EU provided the right amount of economic stimulation while also protecting household incomes. The US and Europe are not conceived of as rivals in Covid-19 recovery and anti-inflation plans, although the fiscal and monetary decisions made on both sides of the Atlantic can and will influence one another (particularly due to the linkage of reserve currencies). Each should therefore pay attention to the actions and macroeconomic forecasts of the other. The US also came up in history lessons from Janse – he explained how the Dutch Guilder was the global reserve currency before it was the British Pound, and is now the US Dollar; but, the euro’s creation has given the Eurozone a way to compete for control in the global financial and monetary markets as the world’s second reserve currency. As the current bout of inflation and recent collapse of some regional banks brings monetary and macro-prudential policy front and center once more amidst claims that the US dollar is slowly declining in its role as the global reserve currency, we might all benefit from taking some meaningful glances at monetary history in its longer perspective. Writing these two blog posts has made me think about what types of issues would garner the most focus if US states were to host a conference amongst various policy experts. Obviously the US is not in need of anything like “treaty” reforms between the states since the US is a complete political, fiscal, monetary, and prudential union. But it is still an interesting intellectual exercise to think about what issues might predominate the discussions, and if/how state and federal action could work in tandem to reduce polarization on some issues in favor of tangible, implementable solutions. Gun control reform, the opioid epidemic, and healthcare costs/equity come top of mind to me as potential areas that might benefit from tempering down the “national” heat and anger that comes from different ideological sides and may benefit from state-level cooperation and task forces to create actionable and politically feasible steps to make real progress. Acknowledgements Thanks Università Bocconi and BLEST for hosting events like this and allowing students to attend! On March 10, Bocconi University in partnership with the BLEST Lab and the Institute for European PolicyMaking hosted The Future of Europe Conference. This very special event brought together high-level representatives of European institutions, member states, and think tanks for a discussion of what Europe’s governance, macroeconomic, and sustainable future looked like. As a student of European politics and institutions, and an American, I wanted to reflect on some of the biggest takeaways and areas of agreement (which were fewer in number than the disagreements :) ) from the panels. Since each of the panels involved lengthy speeches, debates, and (at times) combative Q&A’s with the audience, I have decided to devote separate blog posts to the Governance and Macroeconomics panels. This one focuses on the outcomes from the Governance panel, which was presented by Jean Pierre Vidal (Chief Economic Advisor to European Council Pres. Michel), Brigid Laffan (Emeritus Professor of the European University Institute in Florence), and Sylvie Goulard (Member of France’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and moderated by Prof. Catherine DeVries of Bocconi. These reflections do not represent my own opinions, but those of the speakers and panelists I quote, and is an effort to share and communicate the current mood and thinking of expert Europeans in the present moment.

Reflection #1: Treaty reforms inspired the most enthusiasm, and the biggest ideas. In many ways, the EU’s collective response to Brexit and to the Covid-19 pandemic was seen by the panel as paving the way for serious discussions about treaty reforms to the EU’s institutions. Central to this discussion was how and whether treaty reforms would secure popular support across the EU, how the EU could be made more accountable to European citizens, and the usual ‘unanimity’ versus ‘intergovernmentalism’ debate about EU decision-making. Goulard felt very strongly that the EU would need to end decision-making by unanimity if the EU were to take the hard decisions necessary to avert the climate crisis and stand up to dangerous external threats. She used examples like the hamstringing of the UN Security Council by unanimity rules, and the fact that even university boards are not run by unanimity. Vidal was much more diplomatic, defending how unanimity allows for a representation of all member state interests and states are unlikely to give up their veto power. But questions about how treaty reforms could improve EU accountability were at the heart of these talks. Laffan also turned this topic on its head in some ways, as she brought up how member state governments need to take responsibility for “bringing Europe home” to their citizens and explaining the necessity for reforms to them. As someone experienced in consulting on campaigns for passing EU treaties (in Ireland), she stressed that it becomes the role of national MPs to explain to their constituents what the changes to Europe will offer them. The biggest obstacle, in her view, to MPs' ability to do this was that they often do not understand themselves what the treaties are or mean. These national-level actors therefore need to be trained in the treaties and reforms so that they can “sell” it in their respective member states and communities. Mario Monti, Italy’s Prime Minister (Pres. of the Chamber of Deputies) from 2011-2013, attended the event as a former head of government and former President of Bocconi, and threw in his own ideas for reform of the European Council. PM Monti suggested the European Council adopt a code of conduct to combat the “reprehensive” behavior the member state leaders have towards each other at the table, and even worse behavior in their national press conferences. Interestingly, he also suggested the European Council is the EU institution in most need of urgent reforms. Prof. Laffan suggested in her reply that this might be a good idea. She reasoned that, as a soft instrument, a code of conduct would be a small change that could maybe be snuck in without an outcry from many members of the European Council, but it “becomes a benchmark to at least call out bad behavior.” Monti and Laffan both stressed that the Council should not be “beyond accountability,” and that the appointment of a permanent president has been a good thing for the institution. Vidal thanked both Goulard and Laffan for answering Monti’s suggestion at length so that he could dodge it as current advisor to Pres. Michel! On the topic of EU budgets, strategic action was front-and-center, but not some of the more extreme reforms like the full creation of a federal EU budget. Prof. Laffan thought a larger EU budget will be required to address present risks to the single market. But again, this conversation was quickly brought back to how to make a “European Union of citizens” who must feel fully represented in the decision-making of EU bodies, particularly if they are to take on more power and responsibility, potentially through treaty reforms. Reflection #2: More Europe, but also smarter/“strategic” Europe. This idea of “more Europe,” or even more investments of power and resources in EU institutions, is a serious policy idea, but one that is often discussed with a bit of humor these days because of how often it is brought up. While I would assume all the panelists favor “more Europe,” what was interesting was how there was an even greater focus and commonality in their responses that suggested Europe should hone in on smart and strategic decisions. Prof. Laffan decried how the word “strategic” is increasingly being used in tandem with “Europe,” but without clarity about what exactly this means in mind. In her view, strategic means having EU policy that works, has the capacity to respond to challenges, and some agility since governments are operating in a time of high risk and complexity. From Goulard’s perspective, a smart Europe would have to address the climate change and biodiversity crises first and foremost, as these are the most pressing issues. And while there are serious clashes of preferences between the member states over energy policy and the way forward in the green transition, Goulard emphasized that the EU should not become complacent on national interests. Reflection #3: America was front and center, in good and bad ways. Since geopolitical and security threats were front and center in many of this panel’s talking points, I was surprised that the US was brought up more than Russia or China (although of course both were talked about at length, and the US was framed as a perplexing ally while China and Russia were framed as rising or imminent threats). The chief negative complaint from this panel and the others about the US involved Pres. Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which, in heavily subsidizing green investments in the US, has weakened Europe’s competitive position in the green transition. The IRA was described by Prof. Laffan as a policy “lobbed onto the European table” and risks subsidy competition between the US and EU, which she warned against. In a good way for the EU (but not as great for the US), Vidal also reminded attendees that prices are lower in the EU than the US because of the European single market and competition policy. On the technology side, the US came out as a “winner” from the panel’s discussion. Goulard emphasized how twenty years ago, Europe was ahead of the US on technology, but since then the US made much more investments in tech, and now the EU lags behind the US in technology competition. Vidal went further than Goulard, stating that the EU needed to invest in tech as much as the US and China to remain competitive and maintain innovation. However, this panel happened before the SVB collapse, and I wonder if some of these positions would be more nuanced and also focus on prudential policy health if the discussions were instead held today. In any case, Prof. Laffan felt the EU-US Trade and Technology Council is a dynamic entity that allows for dialogue on technology and other investment decisions and disputes between the two unions, which is important while the European Council tries to address the future of technology in the EU. These are just some of the many highlights of the masterful panel that was chaired by Prof. DeVries. Other topics included the COVID-19 response and health policy, defense policy, “strategic autonomy”, and NATO; and the energy transition, to name a few. Acknowledgements Thanks Bocconi and BLEST for hosting events like this and allowing students of all backgrounds to attend! I was very honored to have the chance to speak on a panel at the Ukrainian Global University’s (UGU) first annual conference as a UGU volunteer. The theme of the conference was “A straight talk about human capital development among students, co-founders, and partners” and the discussion was inspiring and uplifting, even against the sadness and heartbreak of recent strikes on Ukraine that have killed and injured civilians.

The UGU organizers talked about the success of the program, even in its early and initial phase last year, which saw the placement of fifty-two highly talented and advanced Ukrainian students in Western universities. A few UGU students from this first cohort talked honestly about their experiences – from making new friends and meeting new people, to being surprised how many Ukrainian societies/student organizations there are in foreign universities and cities, and some challenges that came with adapting to a new place and a new education system. Undeterred and perseverant, the students were enthusiastic about wanting to return to Ukraine and contribute to its growth and development after the war. Several expressed an interest in joining the civil service and contributing to the ministries of finance and economics. All were steadfast in wanting to learn as much as they can while abroad and teach their peers about Ukrainian culture and history, and then to come home to Ukraine and build a better future for their country. It was also heartwarming to hear from academics and university administration officials that working with UGU had been a highlight of their professional careers, and that their universities were working to ensure they can take more Ukrainian students in the next year, although it is unfortunate that the program needs to continue for yet another academic cycle. A few Deputy Ministers of the Ministry of the Economy and Ministry of Social Policy also spoke at the conference, and it was enlightening and interesting to hear the perspectives of those within the government. The Deputy Minister from the Ministry of the Economy spoke at length about how improving human capital during the war was vital to Ukraine being able to rebuild after the war and the economy’s ability to attract foreign capital and investment. And the representatives from the Ministry of Social Policy echoed the thoughts of the Ministry of the Economy that educational investments for today and tomorrow’s young generations are necessary to protect and strengthen Ukrainian society during and after the war. There were then some claims by the civil society representatives that the government should focus on enacting reforms now, even with the war going on, as opposed to waiting for the reconstruction efforts. Those in the government, however, pushed back and elaborated upon some reform efforts already taking place. In short, there were key points that came out of the discussions and which provide reflections and recommendations for how government and university partners can approach reconstruction, rebuilding, and investments in human capital in Ukraine. The key points:

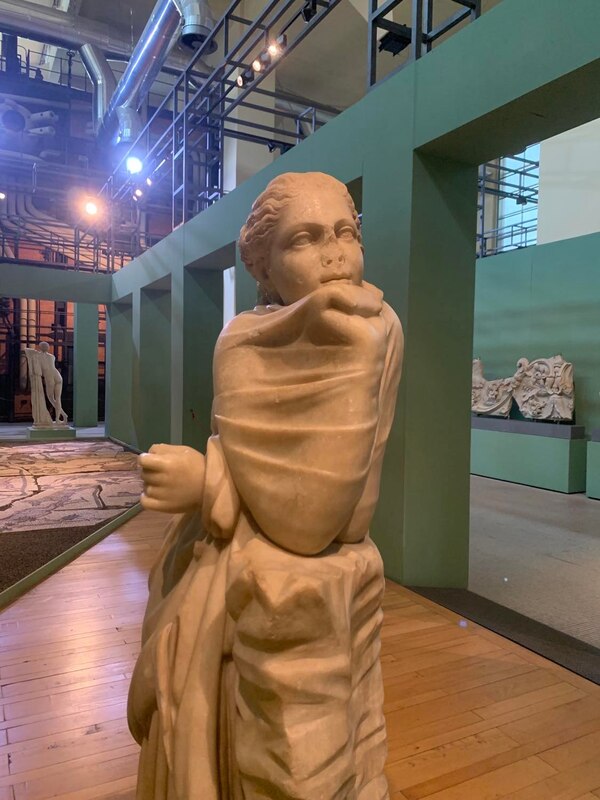

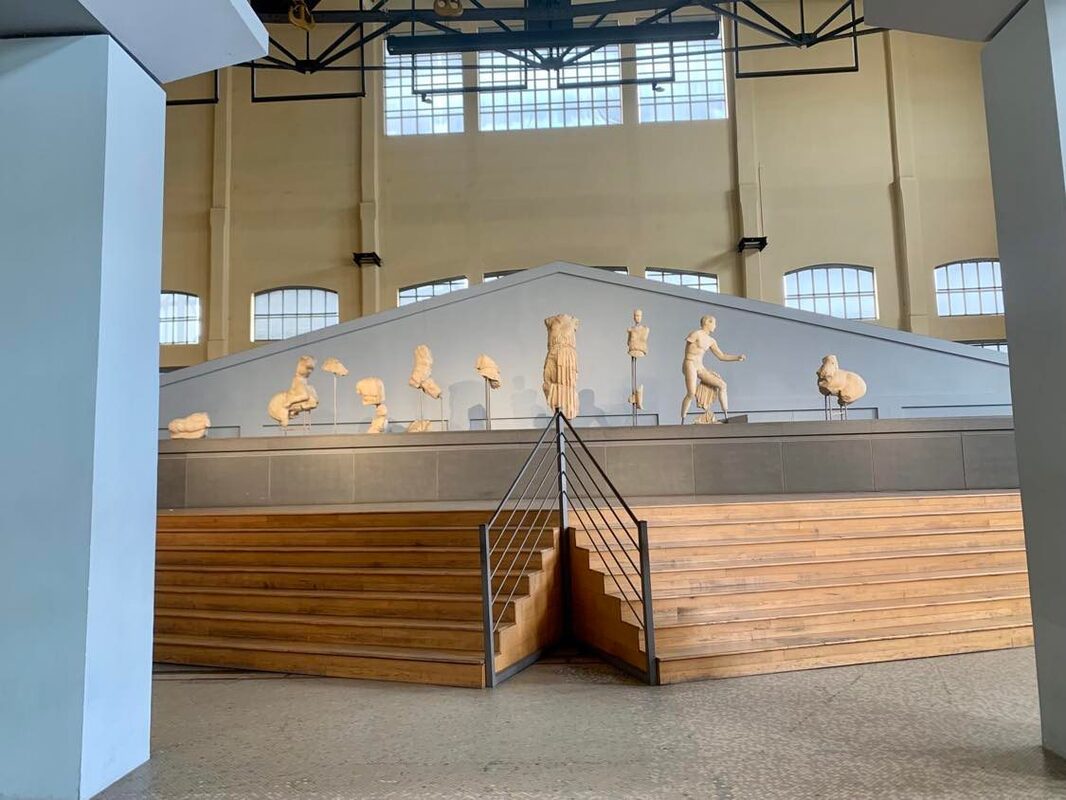

If anyone reading this is interested in volunteering with UGU in the future, please reach out to Dr. Dmytro Iarovyi, other UGU organizers, or myself. Acknowledgements Thank you to the Kyiv School of Economics for the kind and gracious invitation to participate in the UGU conference. I am grateful that I was entrusted to speak on behalf of other incredible volunteers who helped with last summer’s intake of the UGU cohort.  The center point of the “Le macchine e gli dei” exhibit The center point of the “Le macchine e gli dei” exhibit I was very fortunate to have an amazing visit to Rome a few weeks ago, my first in nearly five years! Since I have been a few times before, I decided to see some of the “off the beaten path” places that make Rome special to the locals and natives of Italy’s beautiful capital. One of those places is I Musei Capitolini Centrale Montemartini, an incredibly cool, niche museum located between Ostiense, Garbatella, and Monteverde in Rome. The museum is much revered among locals because it is a transformed industrial factory that now houses archeological artifacts from the Roman republic and empire. The museum is most well-known for its “Le macchine e gli dei” (“The machines and the gods”) exhibition, which opened with the museum in 1997. Located on the top floor of the museum, and with a convenient upper staircase that lets you take in the whole industrial structure and array of storied statues; the scene makes you feel at ease, even if the disquietude of experiencing two worlds colliding should not. The exhibit is so aesthetically appealing that it seemed as if industrial engines and towering statues of Roman deities’ heads were always meant to be compared side-by-side. Of course, this is not an objective truth, and the illusion of their comparability is what makes the museum so fascinating and captivating. The old Franco Tosi boilers and pumps juxtaposed with artifacts of demigods and muses produced a spirit of bellicose tranquility: a unity of opposites. The museum and exhibition also reminds me of “The Divine Image” by William Blake from his Songs of Innocence (1789): “To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love All pray in their distress; And to these virtues of delight Return their thankfulness. For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is God, our father dear, And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is Man, his child and care. For Mercy has a human heart, Pity a human face, And Love, the human form divine, And Peace, the human dress. Then every man, of every clime, That prays in his distress, Prays to the human form divine, Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace...” (Credit: Poetry Foundation) Pity and peace could be found in Polimnia’s gaze, love and mercy in Theseus’s running stance, love and pity in Apollo’s statue, mercy and pity in volcanic Agrippina the Minor, and mercy and peace in the outline of the seated girl. In addition to the incredible statues and industrial equipment, il museo has an extensive and impressive collection of ancient mosaics. The largest one by far, Mosaico con scene di caccia – Mosaic with hunting scenes, is a part of the “Le macchine e gli dei” exhibit. It was lifelike in size and features, and mind-blowing to think how much planning, design, and patience it must have taken to create an image so believable and delicate thousands of years ago. All in all, I musei capitolini centrale montemartini was a terrific, niche find! It gave me the space and time to think about Rome in a different way, with its various history and mythologies scattered about and framed against a more modern era.

Other hidden gems in Rome I recommend visiting:

Acknowledgements Grazie mille to my Roman friends who took me to some great new, authentic places. There is so much to do in Rome, but I am glad I have now explored the infamous and lesser-known spots of “The Eternal City.” Helpful links