|

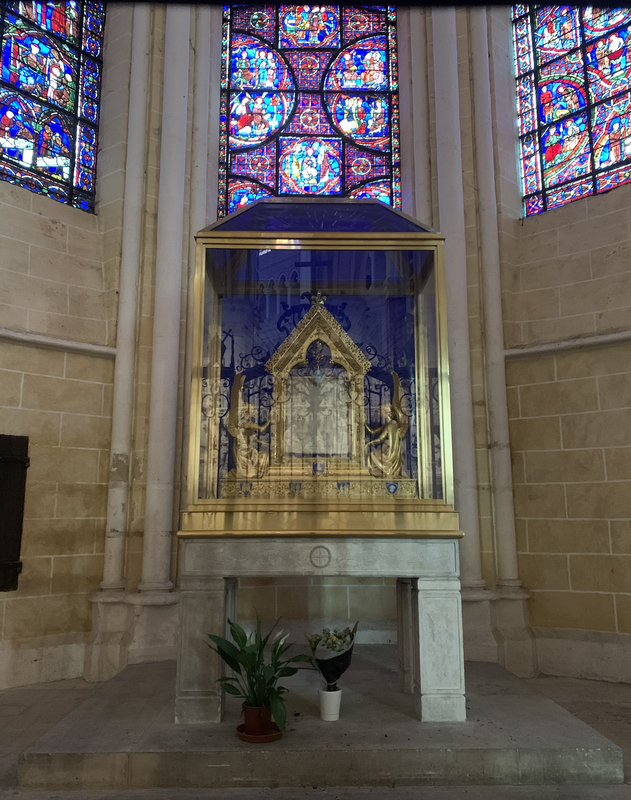

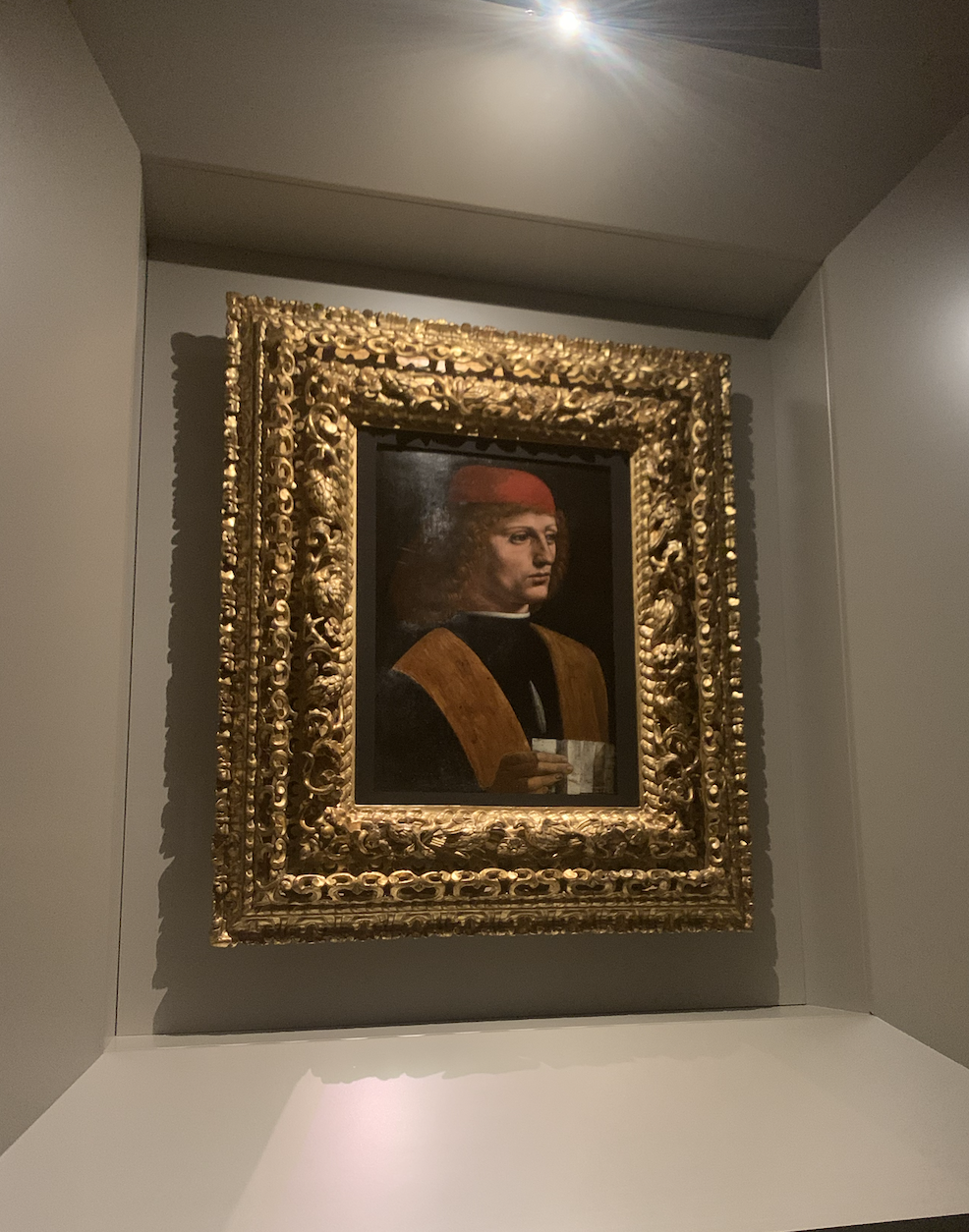

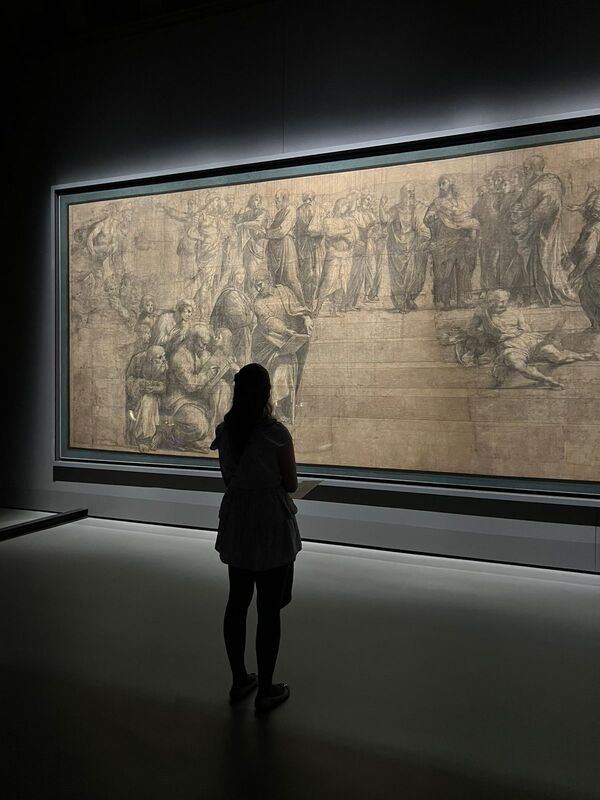

My recent whirlwind trip through 6 countries and 7 time zones in 13 days and with 4 working languages (definitely a new personal record) with nearly all my worldly possessions in tow got me thinking about what makes or breaks an adventure. I was moving from Milan to Berlin via France (to crash my mom’s vacation – more on that later), which required a transatlantic flight to get back to Europe via London, two and a half days to pack and clean a flat, and then a thirteen-hour night bus from Milan to Paris. After the Parisian dream (my first time there!), I then took the Eurostar (my very first!) through France and Belgium to Cologne, and from there continued on a Deutsche Bahn train to Berlin. The night bus experience was certainly made authentic by the French teenager who spent the whole night of travel elbowing me in his sleep or watching TikToks without headphones on. But even with the tiny annoyances like that, plus how the bus drivers smelled profusely of cigarettes the whole ride, the experience was far more magical than grungy. How else can I describe entering France for the first time by reading “Mont Blanc” by Percy Shelley while going through Mont Blanc itself? Or suddenly being jolted awake by a stop in Dijon at 5:30 AM, with the first streams of light breaking over the imposing structure of the Dijon Cathedral? Or falling back asleep, only to wake again to the sight of hay bales in Auxerre that looked like they were lifted straight out of an impressionist masterpiece. (My first thought was, “Wow, they really look like that?!” because somehow, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a hay bale in real life before that moment.) Small, varied, and distant castles then seemed to accompany our bus along the last and final stretch from the countryside to Paris – reaching Vincennes at a still early 9:20 AM. Adventures are full of magic, and the magic comes in letting go of the small bad parts and embracing the spontaneous (and often improvised) good parts. Maybe an adventure is also tagging along on someone else’s for a little while; seeing the world through their eyes, and seeing what they value from their perspective. And then it’s seeing the same thing but finding a different aspect to be remarkable or perhaps even brilliant. For instance, my mom was interested in visiting key places in St. Joan of Arc’s life and death, so we toured Riems, Chartres, and Rouen. Each place had something special: the center of the French monarchy’s coronations in Riems, the Virgin Mary’s veil that was gifted by Charlemagne’s grandson to the village in Chartres, and the burial place of the heart of King Richard the Lionheart in Rouen. But what I found very special was a Calder sculpture that my mom and I literally stumbled on by accident in Rouen outside of the town’s Musée des Beaux-Arts. In elementary school, I fondly remember reading The Calder Game and loving the mind puzzle of connecting clues and art. (The prequel – Chasing Vermeer was equally good if my memory serves me well.) My native Chicago is also the seat of Calder’s Flamingo statue, so I enjoyed thinking that I could be like the main character and decode my surroundings in Chicago and the Midwest. Anyways, seeing an unexpected Calder seemingly so out-of-place in Normandy with its chilly sea-salt-air brought a giant smile to my face. And it reminded me the importance of having exposure to art, stories, and mysteries when you are young. A “room mom” in elementary school used to periodically come into our lessons and teach us about different world famous painters and time periods. She had studied art history before becoming a mom to one of the boys in my class, and would give us biographical information about a painter and then have us interpret or say what we saw in projector images of their most renowned art pieces. (Yep, we still had projectors and no Smart Boards until later.) I remember being thoroughly bored by these lessons – which I feel bad about now that I’m older, a teacher myself, and realize how much time she must have put into volunteering as an art historian – and wondering why I was looking at images of still fruit. In hindsight, however, knowing that art was something I was supposed to appreciate made me slightly more open to it as a grew older, so that by the time I was an adult, I actively wanted to learn more about other cultures and experiences by looking at things like art (and listening to music, reading books in other languages, etc.) Teaching is a sacrifice, as is writing for an audience, and the investments that teachers and authors made into me as a student and reader gave me the ability to make connections, feel a deeper connection to an unknown and new place, and experience happiness many decades later. Adventures are also about endings and beginnings. At the Louvre, I saw Da Vinici’s Mona Lisa with my own eyes. This marked the final major work of Da Vinci’s that I was yet to see! I started a journey to view each of Da Vinci’s most important masterpieces when I took an art history course on Da Vinci and Milan in 2019. I thoroughly enjoyed seeing Da Vinci’s The Last Supper and visiting the tree he used to sit under at what is now a conference center close to Santa Maria delle Grazie, and decided I would try to see each of his great works in my lifetime. This lead me on a five-year journey from Milan to Parma to London to Washington, DC, and finally to Paris with many repeat stops in Milan along the way. (N.b., the Sala delle asse is still not fully open in Milan’s Castello Sforzesco, but I’ve at least finally gotten to see part of it on some recent museum trips. The full room to be experienced later!) I truly expected that this feat would be something that took nearly my entire lifetime to do (or, at least, ten years). Getting to see it all in five years was both an act of intent and a happy accident. (Well, being lucky enough to attend the universities I did/am and to live in Europe at my age sometimes feels like some combination of luck and right timing, as much as it took many years of hard work to get to where I am.) And standing there in front of the Mona Lisa, both further from it and closer to it than I anticipated, I didn’t feel any extreme emotions, simply contentment. Contentment in working hard enough, living life fully enough, and merely being gifted enough blessings in life that I have seen so much beauty and wonder for myself. And reflection and love for all the people that have visited Da Vinci works with me over the last half decade; study abroad friends with whom I saw La Scapigliata in Parma, an old friend who took an early lunch break in DC to see Ginevra de’ Benci with me, my mom who saw The Virgin of the Rocks cartoon in London’s nearly empty National Gallery with me during covid times, etc. Meanwhile, a different journey I inadvertently set myself off on five years ago to collect individual Marshall Plan projects data in West Europe continues with some (more) planned archive trips in Germany leading me to a new and fresh start in Berlin. Whether or not officials recorded – and then left to posterity – highly specific economic records on Marshall Plan disbursements is unfortunately outside of my control, unlike Googling the locations of famous Da Vinci works. If anyone owns a time travel machine, then please let me know.  To celebrate the end of our first quarter, our PhD cohort went to a free quartet performance inside of Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Getting to listen to classical music while sitting next to Da Vinci's Portrait of a Musician was quite spectacular. Thanks to Ximena for capturing this photo of me looking at Raphael's cartoon for The School of Athens afterwards! Finally, a word of redemption for the Parisians and French. After having it drilled into my head by Americans, Brits, and Northern Italians for most of my life that the French/Parisians are the meanest people on earth, they were nothing but the loveliest strangers I have ever met in my life. They went out of their way to help us whenever we needed it, sometimes sat and chatted with us just to be nice, and were all around just deeply, incredibly kind. Perhaps it was post-Olympics euphoria or joy from the optimism the Paralympics brought to town, but we had literally zero negative experiences the entire week; while I’ve had mostly positive experiences in every country I’ve ever visited, each has normally had at least one outlier experience with a stranger. One café owner not only spoke to me in French and was incredibly pleasant to my mom and me, but he also had TTPD playing in the background (if you’re a fellow Swiftie, then you’ll understand the gravity of this.) The Parisians were also far more willing to speak in French with me than the Milanese are to speak in Italian with me some days (and I am nearly fluent in Italian while I am admittedly poor at French still). In Chartres, the café owner and our tour guide even cheered for me when I pulled out some (simple) French. It was the sweetest thing, and I hope the Parisians are an example for how you can encourage someone to keep going, and keep trying. That’s how we open up, show up, and share ourselves and our culture with others. Finally, it made me feel like my London lockdown attempt to teach myself French had not been in vain; another (happy) ending in learning coming back to offer assistance and a gift years later.

0 Comments

|

AuthorSienna Nordquist is a PhD Candidate in Social and Political Science at Bocconi University. She is an alumna of LSE's MSc in European and International Public Policy and was a Robert W. Woodruff Scholar at Emory University. Archives

April 2025

Categories |