|

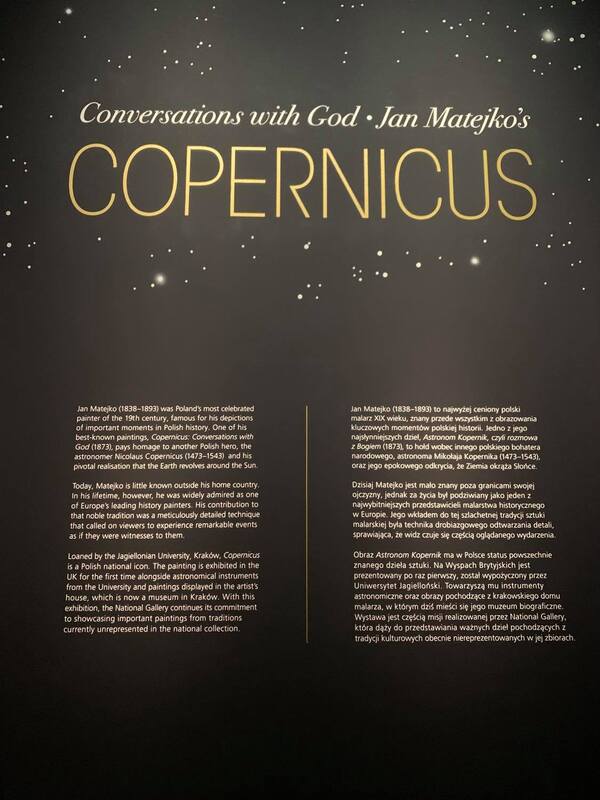

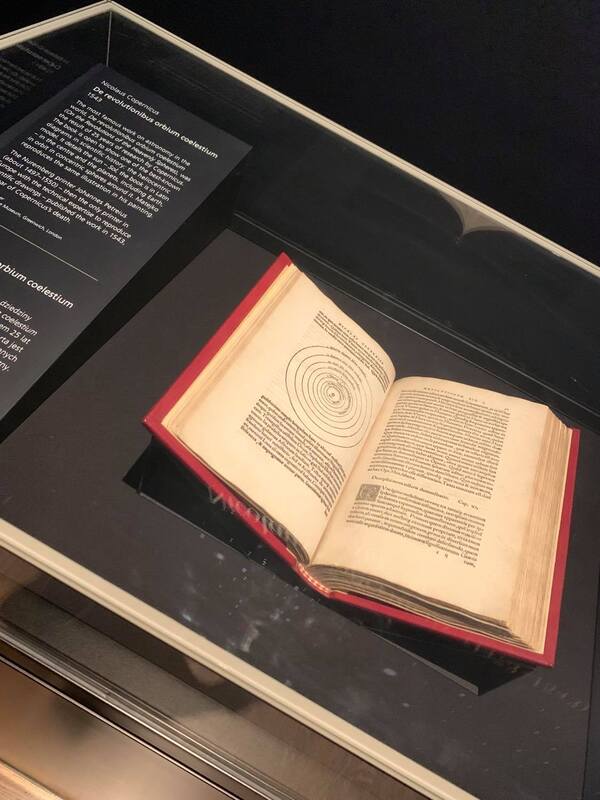

About a month ago, I had the good fortune to see the National Gallery’s (London) Conversations with God exhibit. A dazzling display of the same night sky overshadowing the earth on the evening that Nicolaus Copernicus (also known as Mikołaj Kopernik) died along with Jan Matejko’s most infamous painting at the center of the room, it was a truly spectacular temporary exhibit. Matejko is famous for his paintings and portraits of critical events and scenes in Polish history, and is one of the most revered Polish artists of his time. Well-known paintings of his include Battle of Grunwald, Kosciuszko at the Battle of Raclawice, and King Sigismund II Augustus and Barbara Radziwill. But it was Copernicus, Conversation with God (1873) that drew myself along with many other National Gallery visitors to the exhibit to learn more about Polish art and Matejko’s work in particular. Copernicus appears to be struck by both awe and fear in the painting: both as a reaction to God and to the groundbreaking, earth-shattering (no pun intended) effect of his findings. Holding what appears to be a protractor in his left hand with his notorious heliocentric diagram next to him, as well as several other astronomical tools and dense books spread at his side and feet, Matejko has made the audience feel as if they are looking not only at the soul of Copernicus, but also at all the scientific objects and learning he accumulated throughout his lifetime. The backdrop of the night sky behind Copernicus seems, to me, to be a reference to the sky and scientific field of astronomy the historic man devoted himself to. And it also demonstrates how lonely and isolating his work must have been; to have the skill and mathematical training that he possessed and know that what he discovered would likely elicit backlash or skepticism, from the Church and others. The exhibit speaks to this clash directly in relation to both Copernicus and Matejko’s lives, writing for viewers that “he [Copernicus] never broke with the Church and saw no essential contradiction between science and religion…Copernicus is Poland’s greatest intellectual hero and Matejko its most revered artist and leading patriot. His vision of Poland allowed his compatriots to understand their often troubled history, as well as their unique achievements and the role that religion, especially Catholicism, played in their lives.” Finding unison in these separate forces certainly spoke to me since both science and religion (or more properly, faith) have played a large role in my life, especially in the past five years. (jan-matejko.org 2017; Conversations with God, National Gallery 2021) A deep-seated ability to place science and faith together are evident throughout Copernicus’s life. Indeed, Copernicus’s career pursuits as a young man led him to be close to the Church, or at least to consider joining it. He studied law in Bologna (whose university was one of the most renowned in the western world at the time) in the hopes this would help him begin a Church career. However, young Copernicus became increasingly interested in astronomy and science and so before moving back to Poland in 1503 he first went to Padova and studied medicine. It then seems fitting that a man fascinated with Church doctrine and understanding the universe through science would be the one to use mathematical and astronomical reasoning to show that previous theories were incorrect in their assumptions about where our world stood in the universe, and by extension what it means to be human. In fact, Copernicus was not the first astronomer or mathematician to suggest that the sun is at the center of the universe, but he was the first to ‘prove’ it through mathematical rigor and scientific diagrams. The hard work and effects of time are evident on Copernicus’s face in Matejko’s masterpiece, and some of the ship’s objects appear to be rolling on the ground at his feet while the night air turns the pages of his books, as if the world was both standing still and also slowly making its rightful trip around the sun while Copernicus conversed with God on his findings. Given that Copernicus is the central character of the painting, he is relatively small, which may signify how each of us appear small and misplaced against the vastness of the universe but still at the center of God’s care (even if not the center of the universe). Maybe this is the accordance between science and theology/philosophy that Matejko meant to propose (but really, as someone who isn’t an art historian or scholar, I haven’t the faintest idea and this is purely conjecture!). (Glasgow University Library 2008) Also spread throughout the exhibit room were astrological instruments and one of the original copies of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus erbium coelestium (DREC). DREC contains Copernicus’s novel heliocentric diagram, as well as chapters on movement of the planets, the moon, and trigonometry. The sheer size of the astrolabe is itself astounding, but even more so when you stop and think about all of the thought and understanding about time and the stars that must have gone into crafting each device in the fifteenth century (which brings me to an unrelated recommendation to visit the British Museum’s gallery of old and antique clocks!). (Glasgow University Library 2008) Copernicus’s journey of scientific inquiry and discovery across the European continent, in addition to the diverse origin of the astronomical tools and equipment that surrounded the painting, also demonstrate how discovery and advancement is rooted in sharing knowledge and wisdom across generations and linguistic and cultural divides. Perhaps this is an even greater takeaway than the apparent interconnection between faith and science; that searching empirically and analytically for the truth requires exposure to several disciplines and ways of doing things, along with lots of arduous work.

References Conversations with God. May 21-August 22, 2021. The National Gallery; London, UK. Glasgow University Library. 2008. “Nicolaus Copernicus: De Revolutionibus.” _____<https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/apr2008.html>. Accessed: September 26, _____2021. Jan-matejko.org. 2017. “Jan Matejko: The Complete Works.” <https://www.jan-matejko.org/>. Accessed: September 26, _____2021. Copyright © Sienna Nordquist 2021

0 Comments

Lincoln’s Inn Fields of Holborn and the WC2 how the class of 2021 will miss you for the whole you represented, the hole in time you filled, and your tranquility amidst calamity. Morning walks to the New Academic Building, lunchtime frisbee, evening picnics, late night pass-throughs from drinks in Covent Garden. Humming in the Michaelmas term, so many new arrivals, many others away at home; silent in the Lent term, lockdown quaking in its place; buzzing over Easter, new hopes coming; raucous in the summer, a freedom of fun and anxiety in tandem. The tennis courts the same, the pitter patter of a ball a small certainty in an uncertain time. Deep breaths on the benches, one-on-one conversations two metres apart. New spring leaves, the yellow roses return, Queen Elizabeth’s coronation tree sits on its throne, yoga in the park with friends, we can hug again. Boxers in the gazebo and signs of human strength, graduates and their parents beaming and proud, spread out commencements but dreams filled and lived. Rain in autumn, rain in winter, rain in spring, and rain in summer, the pavement around the four quadrants looks pebbled, stony, and ancient with thunderous downpours, and yet modern and sleek in the drizzling rain, a good adjoining counterpart to the new Marshall Building, started and finished before the pandemic’s expiry date. Resting, sitting, dreaming, wondering, connecting, and maybe crying, healing through the seasons, even when the previous wound was not yet a faded scar. The air and trees and the breeze kept us sane while LSE kept us safe. Lucky in the end, we met friends, saw a few professors’ faces, fell in love with our campus, loved and supported its people even more. The lawn of your inns became ever more crowded, as we waded out and stepped our toes back in to this world we can only hope to change for the better – as you did to us through one another. Pictured below are some of the memories & sights I will cherish most from this year. I am infinitely grateful to the friends and peers that made this year at the LSE special, joyful, and fun – despite the many hardships. Not pictured are many equally wonderful and inspiring friends that couldn't make it to London, as well as amazing professors, fellows, and admin. Let's take lots more photos at graduation! Copyright © Sienna Nordquist 2021

|

AuthorSienna Nordquist is a PhD Candidate in Social and Political Science at Bocconi University. She is an alumna of LSE's MSc in European and International Public Policy and was a Robert W. Woodruff Scholar at Emory University. Archives

April 2025

Categories |